Free and low-cost web development and hosting tools are useful not only for legitimate developers, but also those with more malicious intentions. One such tool, CodeSandbox, describes itself as "an instant IDE and prototyping tool for rapid web development." It allows developers to easily deploy a site or an app, either from code entered directly in the user's sandbox or from a connected GitHub account. This is an attractive feature set for threat actors as well, because it enables them to quickly stand up credential phishing sites with minimal overhead. In the past 90 days, Proofpoint has observed over a thousand credential phishing URLs associated with CodeSandbox, hosted at codesandbox[.]io and csb[.]app, CodeSandbox’s domain for deployments.

How it works

Figure 1: CodeSandbox new sandbox creation template page

Figure 1: CodeSandbox new sandbox creation template page

Proofpoint has detected URLs that are often in the *[.]csb[.]app or *[.]codesandbox[.]io format, where the subdomain represents the name of the project in CodeSandbox. The project names are automatically generated upon sandbox creation.

-

lwdni[.]csb[.]app

-

815ox[.]codesandbox[.]io

-

ticox[.]csb[.]app

-

v8qo2[.]codesandbox[.]io

Using the project name “v8qo2”, we can search within the CodeSandbox project repository to review the source code included in this project and see that this sandbox will be located at https://codesandbox[.]io/s/vigorous-wood-v8qo2.

Figure 2: Project search view

Upon visiting a sandbox URL, expanding the project’s ”Files” section in the left toolbar displays all the files in the project. The files can then be exported as a ZIP file with one click, no authentication required. This is especially valuable to network defenders as the source of the phishing code is frequently not accessible unless an archive has been left behind by the operator.

Contents of one project’s .htaccess and robots.txt files show hallmarks of generic phishkits, such as referer checking and user agent filtering (Figures 3, 4). These measures help operators evade detection by hosting providers, search index bots, or researchers.

Figure 3: .htaccess file for phishing site, here showing various referers that will prompt a request to be redirected somewhere other than the phish page

Figure 4: robots.txt for phishing site, here showing various disallowed user agents

Further examination of the Files directory leads to the ++===.html page, which is JavaScript containing a base64 encoded phishing landing page (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Encoded phishing landing page

Once we decode the base64, the result is more JavaScript containing encoded text.

Figure 6: Decoded JavaScript for phishing landing page

At the end of this JavaScript blob, we find a fromCharCode() function, used here to edit each character and write it out to the document.

![]()

Figure 7: End of decoded JavaScript blob, including use of String.fromCharCode() and document.write(), which further decode and write out the text

Once decoded, this returns the cleartext phishing HTML.

Figure 8: Phishing landing page HTML

An AJAX request is used to create the HTTP POST of stolen credentials to a different site. This common practice helps an actor ensure that if the phish landing page is taken down, the server where the credentials are stored is likely to be unaffected.

Typically, phishkits use PHP on the backend to collect and process the data, along with phpmail to ship stolen credentials to the operator. Because CodeSandbox does not host PHP, this will likely continue to be hosted elsewhere. In this case, the URL points to a subdomain provided by DynDNS, a free dynamic DNS service. This further illustrates that the operator is taking steps to be evasive and cost-effective.

Figure 9: AJAX request to a site hosted on dyndns[.]dk; if the user-supplied credentials are deemed ’invalid‘, the user will be redirected to google[.]com

Putting it all together

Once the phish page is functional, lures are crafted and sent to direct traffic to the page.

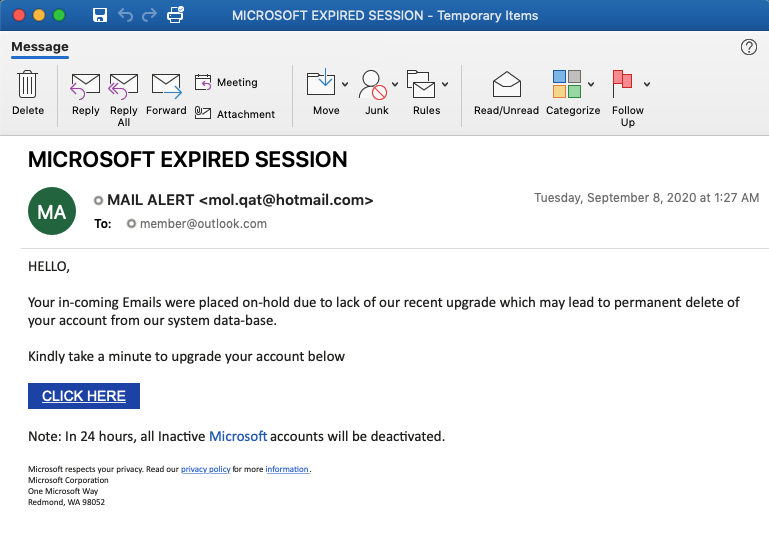

Figure 10: Email lure impersonating Microsoft, suggesting that the recipient’s account might be deactivated if they don’t login within the following 24 hours

Clicking “Click Here” in the lure above (Figure 10) takes the user to an Outlook credential phishing page hosted on csb[.]app (Figure 11).

Figure 11: Outlook credential phishing landing page

Figure 12: Email lure suggesting that a document has been shared with the recipient

The “Open” button in the lure above (Figure 12) leads to a Microsoft credential phishing page (Figure 13).

Figure 13: Microsoft credential phishing landing page

Other phishing pages

Below is a sample of other credential phishing landing pages we’ve observed on CodeSandbox.

Conclusion

Hosting phishing pages on web-based sandbox environments has advantages for threat actors and researchers alike, as well as drawbacks. The quick setup and minimal infrastructure overhead simplify the credential phishing process for an actor. Hosting on the domain of a legitimate development tool makes it less likely–even if only slightly–that an organization will block the domain outright, compared to phish pages hosted on custom domains.

Reviewing the history of csb[.]app, the domain has a history of frequent suspensions for abuse and compliance issues. CodeSandbox does not appear to have visible abuse public reporting such as an abuse@ alias or an abuse complaint submission form. In some cases, sites are reported via Twitter, where the host appears to respond and remove the offending content.

As with any tool that’s made to be simple for the intended user, an unintended consequence is that such resources are often simple for threat actors to use and abuse as well–interactive sandbox environments included.

Emerging Threats / Emerging Threats Pro Signatures

-

2030603 - Possible Phishing Landing Hosted on CodeSandbox.io M1

-

2030604 - Possible Phishing Landing Hosted on CodeSandbox.io M2

-

2030605 - Possible Phishing Landing Hosted on CodeSandbox.io M3

-

2030606 - Possible Phishing Landing Hosted on CodeSandbox.io M4