Table of Contents

Definition

Smishing is a cyber-attack that targets individuals through SMS (Short Message Service) or text messages. The term is a combination of “SMS” and “phishing.”

In a smishing attack, cybercriminals send deceptive text messages to lure victims into sharing personal or financial information, clicking on malicious links, or downloading harmful software or applications. Just like email-based phishing attacks, these deceptive messages often appear to be from trusted sources, and they use social engineering tactics to create a sense of urgency, curiosity, or fear to manipulate the recipient into taking an undesired action.

Most of the 3.5 billion smartphones worldwide can receive text messages from any number in the world. Many users know the dangers of clicking a link in email messages. However, fewer people are aware of the risks of clicking links in text messages. Users are much more trusting of text messages, so smishing is often lucrative to attackers phishing for credentials, banking information and private data.

Cybersecurity Education and Training Begins Here

Here’s how your free trial works:

- Meet with our cybersecurity experts to assess your environment and identify your threat risk exposure

- Within 24 hours and minimal configuration, we’ll deploy our solutions for 30 days

- Experience our technology in action!

- Receive report outlining your security vulnerabilities to help you take immediate action against cybersecurity attacks

Fill out this form to request a meeting with our cybersecurity experts.

Thank you for your submission.

How Smishing Works

Most smishing attacks work like email phishing. These attacks use a combination of technological manipulation and psychological tactics to deceive victims. The following steps outline the general process:

- Target Selection: Cybercriminals choose their targets. This selection can be random, using a broad list of phone numbers, or more specific, targeting individuals based on data obtained from previous breaches or information sold on the dark web.

- Crafting the Message: The attackers create a deceptive text message that invokes a specific emotion or reaction, such as urgency, fear, or curiosity. This message typically includes a call to action, like clicking a link or calling a number.

- Message Delivery: Using SMS gateways, spoofing tools, or infected devices, the attacker sends out the smishing message to their selected targets.

- Interaction: Upon receiving the message, it prompts the victim to take action. This could be clicking on a provided link, replying with personal information, or calling a specified phone number.

- Data Collection or Malware Deployment: Several outcomes can occur if the victim interacts as the attacker hopes. They might land on a fraudulent website where they input personal or financial data. Or they could unknowingly download malicious software onto their device. If they call a number, the attacker might trick them into providing information verbally or incurring charges.

- Use of Stolen Information: With the desired information in hand, the attacker can use it for various malicious purposes, such as identity theft, unauthorized transactions, selling the data on the black market, or further targeted attacks.

- Evasion: To continue their operations undetected, attackers frequently change their tactics, use different phone numbers, and employ various techniques to mask their identity and location.

Smishers use a variety of ways to trick users into sending private information. For example, they may use basic information about the target (such as name and address) from public online tools to fool the target into thinking the message is from a trusted source.

The smisher may use your name and location to address you directly. These details make the message more compelling. The message then displays a link pointing to an attacker-controlled server. The link may lead to a credential phishing site or malware designed to compromise the phone itself. The smisher then uses the malware to snoop the user’s smartphone data or send sensitive data silently to an attacker-controlled server.

Social engineering, in combination with smishing, makes for a powerful attack. The attacker might call the user asking for private information before sending a text message. The disclosed information is then used in the smisher’s text message attack. Several telecoms have tried to fight social engineering calls by displaying “Spam Risk” on a smartphone when a known scam number calls the user.

Basic Android and iOS security features often prevent malware. But even with robust security controls on mobile operating systems, no security control can combat users who willingly send their data to an unknown number.

Types of Smishing Attacks

Similar to the rising sophistication of conventional phishing attacks, smishing schemes come in many elaborate forms. Common types of smishing include:

- Account Verification Scams: In this type of attack, the victim receives a text message claiming to be from a reputable company or service provider, such as a bank or a shipping carrier. The message typically warns users about unauthorized activity or asks them to verify account details. When users click the provided link, they’re directed to a fake login page, where their credentials can be stolen.

- Prize or Lottery Scams: Here, an attacker informs victims they’ve won a prize, lottery, or sweepstakes. To claim their prize, they must provide personal details, pay a small fee, or click on a malicious link. The goal is either to steal sensitive information or money.

- Tech Support Scams: Users receive a message warning them about a problem with their device or account with a request to contact a tech support number. Calling this number can lead to charges, or the “technician” may request remote access to the device, leading to potential data theft.

- Bank Fraud Alerts: These messages appear to come from the victim’s bank, warning about unauthorized transactions or suspicious activities. The user is then prompted to click on a link to verify their transactions or call a number, both controlled by the attacker.

- Tax Scams: Around tax season, many people receive messages claiming to be from tax agencies. These messages often promise tax refunds or threaten penalties for supposedly unpaid taxes, urging the recipient to provide personal or financial details.

- Service Cancellation: The attacker warns the victim that a subscription or service (like a streaming service or software subscription) is about to be canceled due to a payment issue. They’re urged to click on a link to “resolve” the issue, which usually leads to a phishing page.

- Malicious App Downloads: Users receive a message promoting a useful or entertaining app. Clicking on the download link leads to installing malicious software on the user’s device.

Awareness of these common smishing tactics can significantly reduce the chances of falling victim to them. Always cautiously approach unexpected or suspicious messages, verify them with the claimed source using known contact methods, and avoid clicking on unfamiliar links or downloading files from unknown senders.

Smishing vs. Phishing vs. Vishing

Understanding the differences between Smishing, Phishing, and Vishing is vital for awareness and protection against a wide range of cyber threats. Each term refers to deceptive tactics cybercriminals use to trick individuals into divulging sensitive information. However, each approach uses different mediums and methods to carry out the attack.

Smishing

- Medium: SMS (Short Message Service) or text messages.

- Method: Cybercriminals send deceptive text messages attempting to lure victims into sharing personal or financial information, clicking on malicious links, or downloading harmful software.

- Example: A text message alerting the recipient of a suspicious bank transaction and urging them to click a link to verify their account.

Phishing

- Medium: Primarily email but can also include malicious websites and social media.

- Method: Cybercriminals craft fraudulent emails to appear as if they come from reputable sources. These emails often contain malicious links or attachments and are designed to trick recipients into providing sensitive data, such as login credentials or credit card numbers.

- Example: An email, seemingly from a popular e-commerce site, asking users to reset their passwords due to a security breach, leading to a fake login page.

Vishing (Voice Phishing)

- Medium: Voice calls (via traditional telephone or VoIP services).

- Method: Cybercriminals impersonate legitimate organizations, such as banks or government agencies, over the phone. They aim to extract sensitive information directly from the victim during the call.

- Example: A call from someone claiming to be from the IRS, stating that the victim owes back taxes and will face legal consequences unless they make an immediate payment.

In simple terms, phishing is a broader umbrella term that often focuses on deceptive emails and websites. Smishing is a form of phishing that specifically targets users through text messages. Vishing exploits voice communication, typically over phone calls.

Reduce Phishing Susceptibility With Proofpoint Phishing Awareness Training

Examples of Smishing Attacks

Many attackers use an email address to automate sending text messages and avoid detection. The phone number listed in caller ID usually points to an online VoIP service such as Google Voice, where you can’t look up the number’s location.

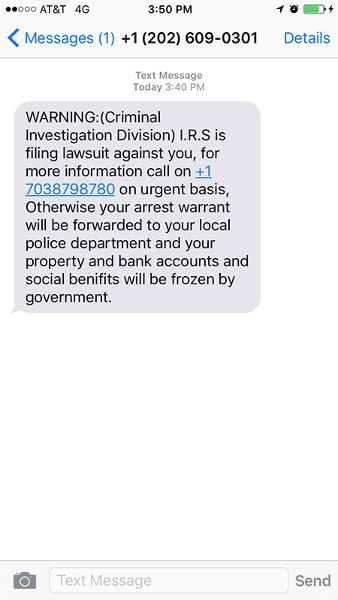

The following image displays a sample smishing attack. Here, the attacker poses as the IRS and threatens the recipient with arrest and financial ruin unless they call the number in the text. If the recipient calls, they are scammed into sending money.

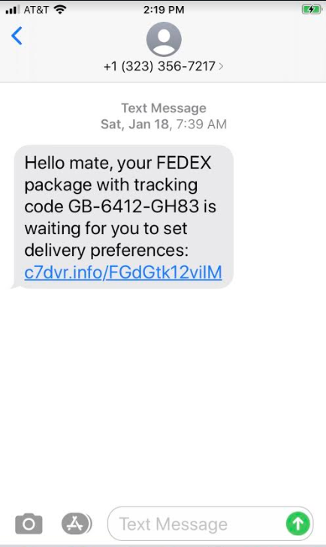

A more common smishing attack uses brand names with purported links to the brand’s site. Usually, an attacker tells the user that they’ve won money or provides a malicious link for tracking packages, as in the following example.

The language in the above message should be a warning sign for users familiar with how smishing works. However, many users trust SMS messages and aren’t alerted by informal language.

Another warning sign is the URL: it does not point to an official FedEx URL. But, not all users are familiar with official brand URLs and may ignore them.

Attackers use this type of message because FedEx package deliveries are prolific. A message sent to thousands of recipients will likely trick many of them.

The link typically points to a site hosting malware or prompts users to log in to their account. The authentication page is not on the official FedEx site, but seeing the full URL on a smartphone browser is more difficult, and many users won’t bother checking.

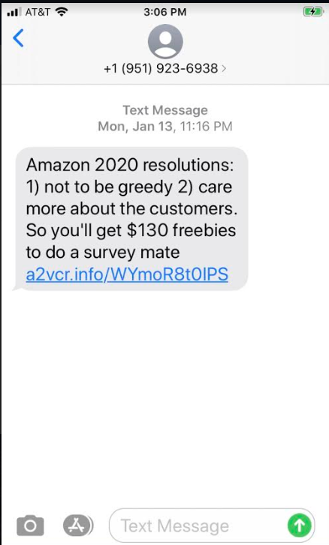

Smishing attackers send users unexpected messages. Others lure victims with promises of prize money upon entering private information. The following image is another smishing attack using Amazon’s brand name:

Again, the language in the above attack should make recipients suspicious, but users trust informal conversations in text. The link in this message points to a .info site unrelated to Amazon web properties.

The domain has already been removed and is no longer accessible. But chances are the link pointed to a page that attempted to collect private data, including credentials. The URL in these attacks usually redirects users to an attacker-controlled server displaying the phishing content.

Based on some of the most common types of smishing schemes, below are additional examples of how smishers craft these text messages.

- Banking Scams: “Dear [Bank Name] customer, we’ve detected unusual activity on your account. Please click the link to verify your transactions: [malicious link].”

- Parcel Delivery Scams: “Hello, this is [Courier Service]. We’ve attempted to deliver your package today but failed. Schedule your redelivery here: [malicious link].”

- Account Verification Scams: “We detected a login attempt from an unfamiliar location. If this wasn’t you, please secure your account here: [malicious link].”

- Contest Winner Scams: “You’re the lucky winner of our grand prize! Register here to receive your reward: [malicious link].”

- Emergency Scams: “A family member of yours has been in an accident. Call this premium rate number for details: [malicious phone number].”

As you can see from the examples above, psychology and social engineering are the framework behind most smishing attacks.

How to Identify and Prevent Smishing Attacks

Like email phishing, protection from smishing depends on the targeted user’s ability to identify a smishing attack and ignore or report the message. A telecom might warn users who receive messages from a known scam number or drop the message altogether.

How to Detect Smishing Scams

Smishing messages are dangerous only if the targeted user acts on them by clicking the link or sending the attacker private data. Here are a few ways to detect smishing and avoid becoming a victim:

- The message offers quick money from winning prizes or collecting cash after entering information. Coupon code offerings are also popular.

- Financial institutions will never send a text asking for credentials or a money transfer. Never send credit card numbers, ATM PINs, or banking information to someone via text messages.

- Avoid responding to a phone number that you don’t recognize.

- A sender number with only a few digits probably came from an email address, a sign of spam.

- Banking information stored on a smartphone is a target for attackers. Avoid storing this information on a mobile device. This banking information could be compromised if an attacker installs malware on your smartphone.

- Telecoms offer numbers to report attacks. To protect other users, send the message to your telecom’s number so that it can be investigated. The FCC also takes complaints and investigates text message scams.

How to Prevent Smishing Attacks

Given the widespread nature of these attacks, preventing smishing requires a combination of technological, organizational, and individual actions. Let’s look at various solutions across these categories:

Technological Solutions:

- SMS Filtering: Many smartphones and carriers now provide SMS filtering options to identify and block or flag suspicious texts.

- Multifactor Authentication (MFA): Even if attackers obtain some credentials through smishing, using MFA is an additional protective layer.

- Anti-phishing Tools: Some security applications for mobile devices can help identify phishing links in text messages and prevent users from accessing malicious sites.

Organizational Solutions:

- Education and Awareness: Regular training sessions on cybersecurity threats, including smishing, can empower employees or members of an organization to recognize and report suspicious messages.

- Reporting Mechanisms: Establish clear channels for employees or stakeholders to report potential smishing attacks. These reports enable the organization to issue warnings if a specific smishing campaign targets them.

- Simulated Smishing Tests: Just as organizations conduct simulated phishing tests via email, they can also send fake smishing messages to see how recipients respond. These tests identify areas where more training might be necessary.

- Regular Updates: Keep software, including mobile operating systems and security tools, up to date to defend against the latest known threats.

Individual Solutions:

- Never Click Suspicious Links: If you receive an unexpected or suspicious text, refrain from clicking on any links or downloading attachments.

- Verify Independently: If a text claims to be from a specific organization or individual, contact that entity directly using known contact information, not the details provided in the text.

- Use Phone Security Features: Take advantage of built-in security features, like biometric authentication and regular software updates, to keep personal data secure.

- Stay Updated: Be aware of current smishing tactics and threats. Awareness can be your first line of defense.

- Don’t Share Personal Information: Never share personal, sensitive, or financial information via text unless you initiated the conversation and are certain about the recipient’s identity.

- Check for Official Communication: Official organizations, especially banks and government agencies, typically don’t ask for personal information via text. If in doubt, call the organization directly.

While these solutions can significantly reduce the risk of falling victim to a smishing attack, no measure is entirely foolproof. Continuous vigilance and a healthy dose of skepticism are crucial in the fight against these and other cyber threats.

How Proofpoint Can Help

Proofpoint is a leading cybersecurity company that offers a suite of advanced solutions to protect against a range of threats, including smishing. Proofpoint helps combat these scams through the following capabilities and features:

Protection Across Email, Social, and Mobile

- Unified Protection: Proofpoint offers a holistic approach by providing protection not just for email but also for social media and mobile channels. Since attackers can exploit any of these avenues, unified protection is essential.

- Targeted Attack Protection (TAP): TAP helps detect, analyze, and block advanced threats across multiple channels. So, Proofpoint can identify and counteract a malicious link in a text message or a risky app on an employee’s smartphone.

- Intelligent Analysis: Proofpoint’s solutions use advanced threat intelligence and machine learning to discern between legitimate communications and potential threats. This is pivotal in detecting newer, evolving smishing tactics.

Mobile Threat Assessment

- Risk Analysis: With its Mobile Threat Assessment, Proofpoint offers a comprehensive view of potential mobile threats for an organization. These threats include smishing attacks, risky mobile apps, and unsecured Wi-Fi connections. By identifying these risks, organizations can take proactive steps to mitigate them.

- Visibility Into Attack Vectors: Proofpoint provides insights into which mobile devices and apps are at risk. This visibility helps organizations secure potentially vulnerable entry points for attackers to exploit via smishing or other mobile threats.

- Threat Context: Proofpoint doesn’t just highlight threats; it also provides detailed context. This means organizations get a deeper understanding of the nature of the threat, its potential impact, and how best to counteract it.

- Custom Recommendations: After analyzing an organization’s threat landscape, Proofpoint offers tailored recommendations on bolstering security. This tailored approach ensures that defenses align with an organization’s unique risks and challenges.

Proofpoint offers a multi-layered approach to counter-smishing and other related threats. By combining advanced analytics, real-time threat intelligence, and unified protection across multiple channels, Proofpoint ensures that organizations navigate the digital landscape confidently and securely. For information, contact Proofpoint.