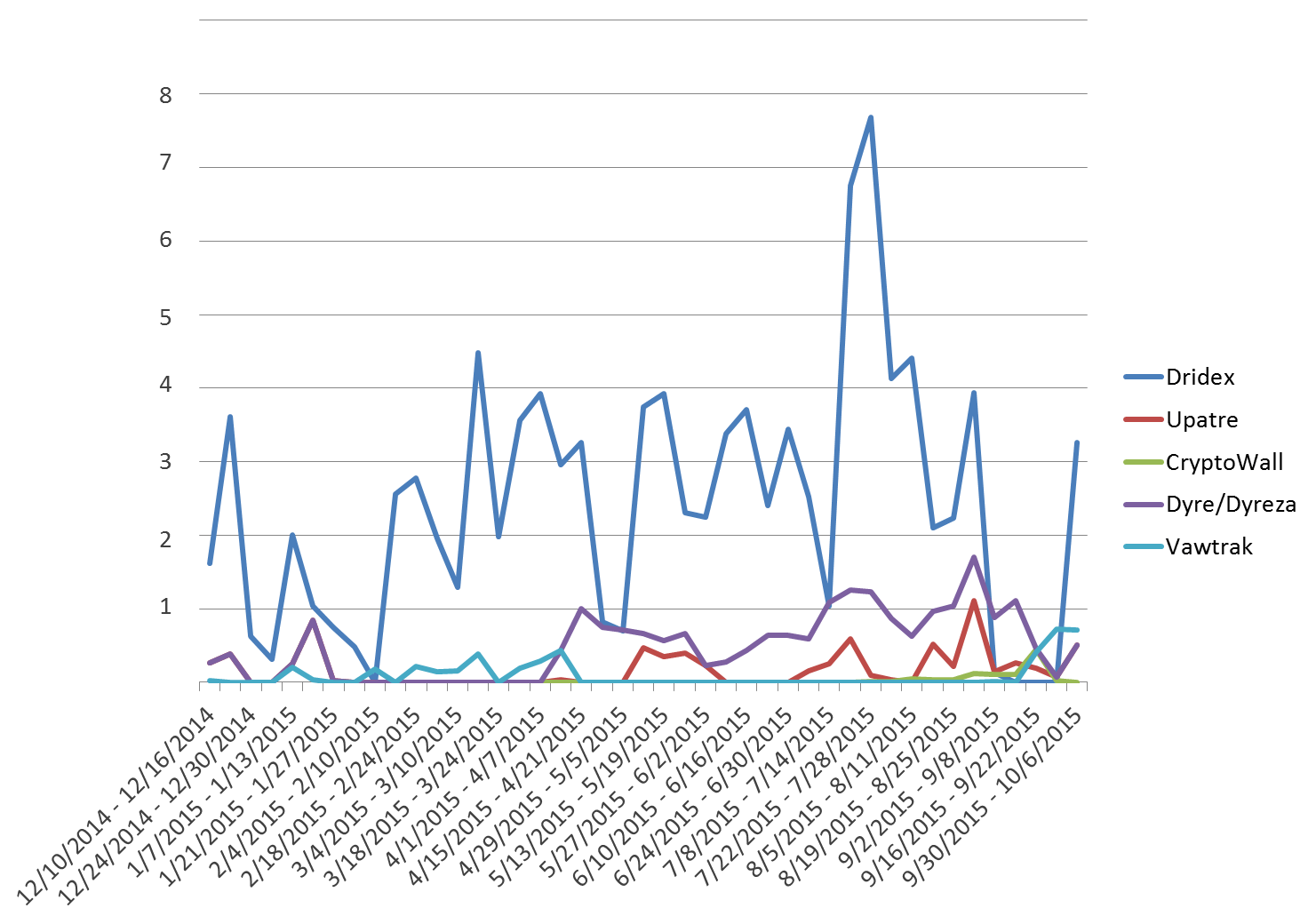

The early-September arrest of a member of the group behind the Dridex banking Trojan [1] led to speculation whether the waves of Dridex-bearing phishing campaigns [2] would abate or disappear altogether. Considering the massive volume of these campaigns, any letup would have been both noticeable and welcome, and the ensuing quiet period was clearly visible in the daily volume of malware monitored by Proofpoint researchers. (Fig. 1)

Figure 1: Indexed weekly phishing document attachment malware volume, by payload

From approximately September 1 Dridex activity all but disappeared, and remained quiet for almost exactly thirty days, until an October 1 campaign marked the end of this hiatus. Analysis of these new payloads revealed – as has already been noted elsewhere [3] – that they were otherwise unremarkable compared to pre-hiatus Dridex payloads. An October 6 campaign showed the same traits, so it remains to be seen whether the continuous innovation that has been a hallmark of the Dridex campaigns during the first part of 2015 will resume.

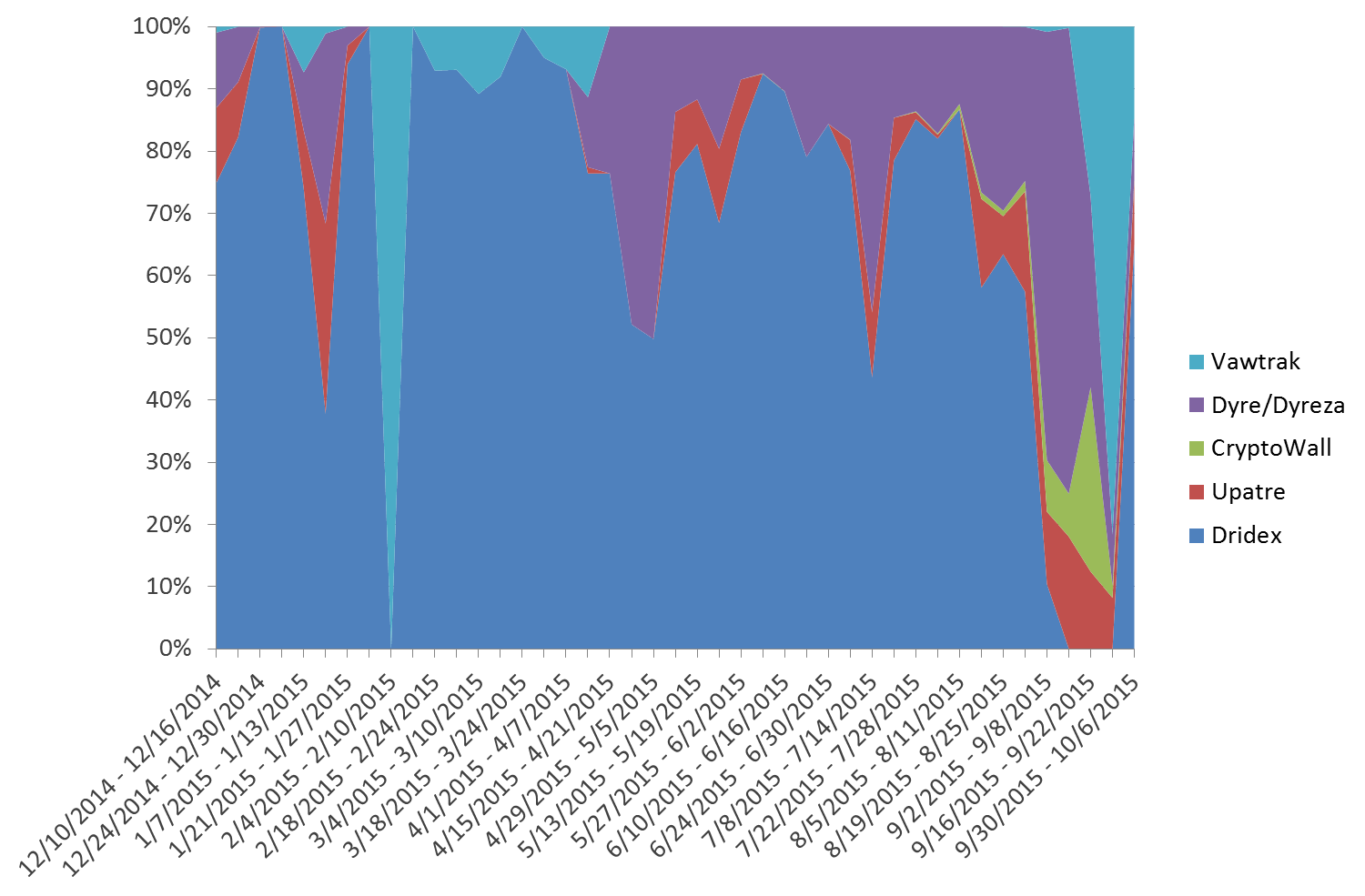

But what happened to malware payloads during the Dridex hiatus? Did they remain the same, or did the absence of Dridex create an opportunity for other malware authors, a vacant niche in the malware ecosystem, so to speak? Our recent analysis of Vawtrak [4] identified numerous changes that seemed to make it a candidate to fill the void left by Dridex. Looking at chart in Figure 1, it seems that the volumes of other payloads remained relatively unaffected by the Dridex hiatus, but the relative volume of Dridex obscures variations in other payloads. Charting the most common malware payloads as a percentage of total activity gives a better view. (Fig. 2)

Figure 2: Weekly phishing document attachment malware payloads as a percentage of total malware

Viewed from this angle, it becomes evident that the main beneficiaries of the Dridex hiatus were initially Dyre (aka Upatre) and CryptoWall 3.0, which then ceded to a resurgent Vawtrak [5], as suspected. Moreover, Dyre has been steadily present and exhibited brief surges over the past ten months, but CryptoWall and Vawtrak had both been largely absent from phishing payloads in significant numbers for at least six months, so in raw terms these two were the most direct beneficiaries of the Dridex hiatus. Even if their overall volume did not approach that of the Dridex campaigns, the sudden change in payload can represent a significant challenge for defenses that have adapted to months of Dridex payloads.

Interestingly, volumes for all three have fallen dramatically with the return of Dridex, raising the question of whether their moment in the spotlight as a phishing payload has passed.

Analysis of phishing malware payloads during the Dridex hiatus thus highlights several key traits:

- Threat actors are adept at substituting one ecosystem component for another, and there are many options available to them at any given time.

- “Old” threats are never far away: Just because a particular malware payload has not been detected in months does not mean that it is no longer a threat.

- Malware is flexible: Payloads that normally spread via one vector – such as CryptoWall via malvertising – can quickly ‘jump’ to other distribution vectors when the need and opportunity arise.

References

[1] http://krebsonsecurity.com/2015/09/arrests-tied-to-citadel-dridex-malware/

[2] https://www.proofpoint.com/us/threat-insight/post/Top-Trends-of-2015

[3] http://researchcenter.paloaltonetworks.com/2015/10/dridex-is-back-and-targeting-the-uk/

[4] https://www.proofpoint.com/us/threat-insight/post/In-The-Shadows

[5] http://blogs.technet.com/b/mmpc/archive/2015/08/11/msrt-august-2015-vawtrak.aspx