Overview

Proofpoint researchers track a wide range of threat actors involved in both financially motivated cybercrime and state-sponsored actions. One of the more prolific actors that we track - referred to as TA505 - is responsible for the largest malicious spam campaigns we have ever observed, distributing instances of the Dridex banking Trojan, Locky ransomware, Jaff ransomware, The Trick banking Trojan, and several others in very high volumes.

Because TA505 is such a significant part of the email threat landscape, this blog provides a retrospective on the shifting malware, payloads, and campaigns associated with this actor. We examine their use malware such as Jaff, Bart, and Rockloader that appear to be exclusive to this group as well as more widely distributed malware like Dridex and Pony. Where possible, we detail the affiliate models with which they are involved and outline the current state of TA505 campaigns.

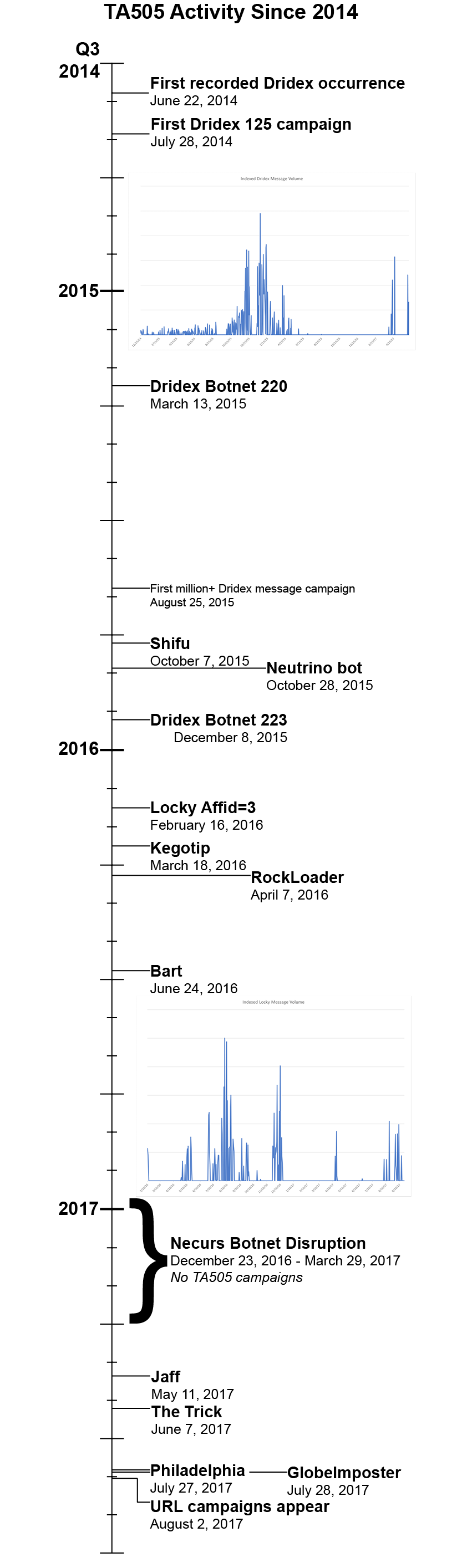

The infographic in Figure 1 traces the earliest known dates on which TA505 began distributing particular malware strains, beginning with Dridex in 2014 and most recently when they elevated GlobeImposter and Philadelphia from small, regionally targeted ransomware variants to global threats.

Figure 1: Timeline of TA505 malware introductions

Of note is TA505’s use of the Necurs botnet [1] to drive their massive spam campaigns. As we saw in both 2016 and 2017, disruptions to Necurs went hand-in-hand with quiet periods from TA505. When the botnet came back online, TA505 campaigns quickly returned [2], usually at even greater scale than before the disruption.

The following is a more detailed description of the malware and notable campaign attributes associated with TA505.

Dridex

The now infamous Dridex banking Trojan can trace much of its DNA to Cridex and Bugat [3]. Dridex itself appeared shortly after the Zeus banking Trojan was taken down. It was originally documented [4] on July 25, 2014 (or June 22, 2014, according to Kaspersky [5]) and the first campaign we observed in which TA505 distributed Dridex occurred three days later on July 28. Although a number of actors have distributed Dridex, TA505 operates multiple affiliate IDs, including what appears to be the earliest recorded affiliate, botnet ID 125. These early campaigns were distributed via the Lerspeng downloader while later campaigns occasionally used Pony or Andromeda as intermediate loaders to distribute various instances of Dridex.

Although TA505 initially distributed Dridex botnet ID 125, they were observed using botnet ID 220 in March 2015 and botnet ID 223 in December of that year. Later, they were also associated with botnet IDs 7200 and 7500. These botnets generally target the following regions:

- 125: UK, US, and Canada

- 220: UK and Australia

- 223: Germany

- 7200: UK

- 7500: Australia

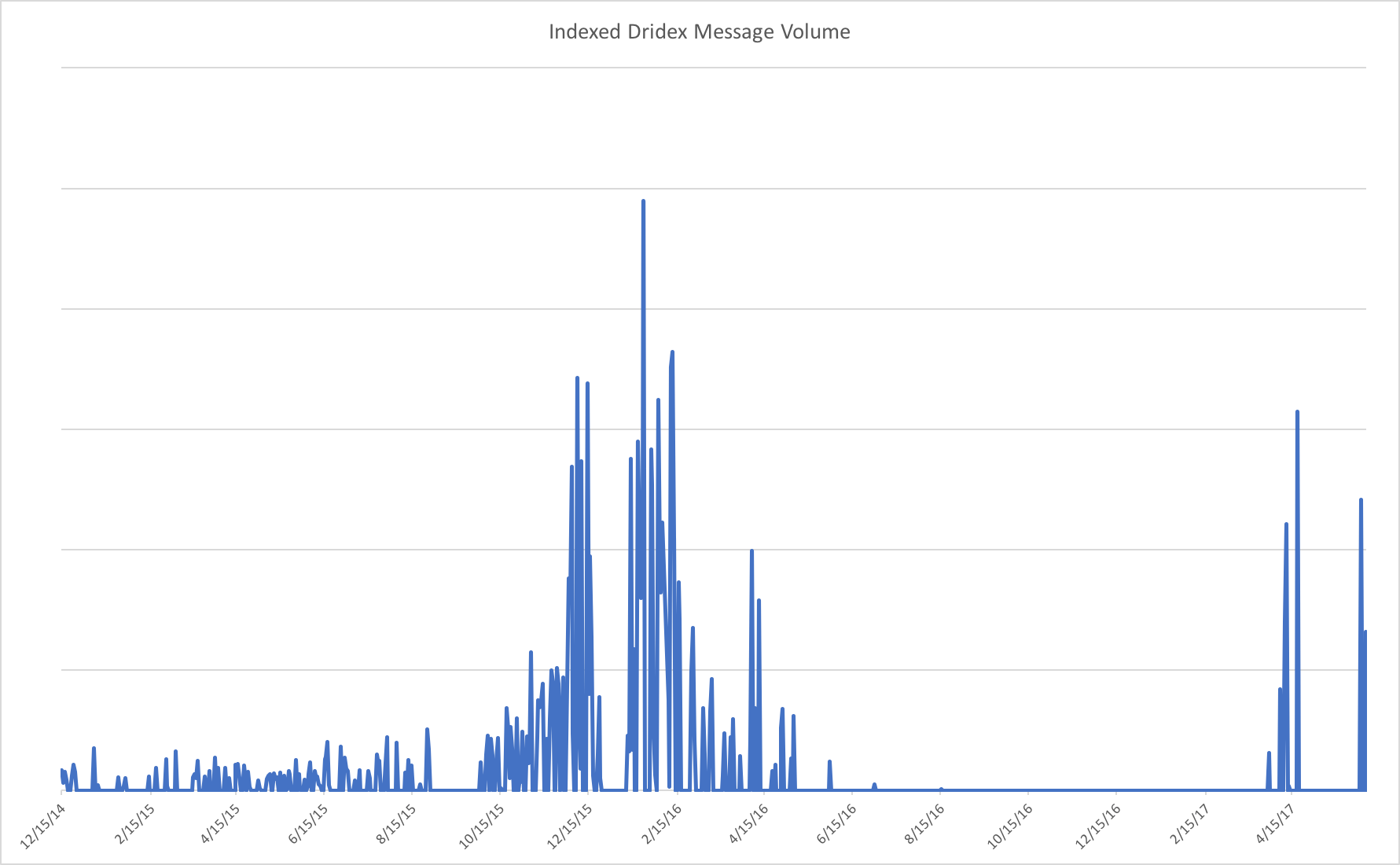

The group has routinely distributed the malware in larger campaigns than any other actor, regularly spamming millions of recipients.

Figure 2: Indexed Dridex message volume since TA505 began distributing the banking Trojan in 2014

TA505 continued distributing Dridex through early June 2017 using a range of email attachments. Most recently these included PDF attachments with embedded Microsoft Word documents bearing malicious macros that call PowerShell commands that install Dridex. However, because of the length of time for which the group has been distributing Dridex, distribution mechanisms trace the state of the art for the last two years of email campaigns with techniques ranging from straight macro documents to a variety of zipped scripts.

Shifu

In October 2015, we observed several campaigns in which TA505 targeted Japanese and UK organizations with the Shifu banking Trojan [6]. Shifu is relatively common in Japan but was a new addition to TA505’s toolbox. It appears that they introduced Shifu after high-profile law enforcement actions impacted Dridex distribution. However, TA505 was also among the first actors to return to high-volume Dridex distribution this same month, even as they demonstrated their ability to diversify and deliver threats beyond Dridex.

As with many of their other campaigns, TA505 delivered Shifu through macro-laden Microsoft Office document attachments.

Locky

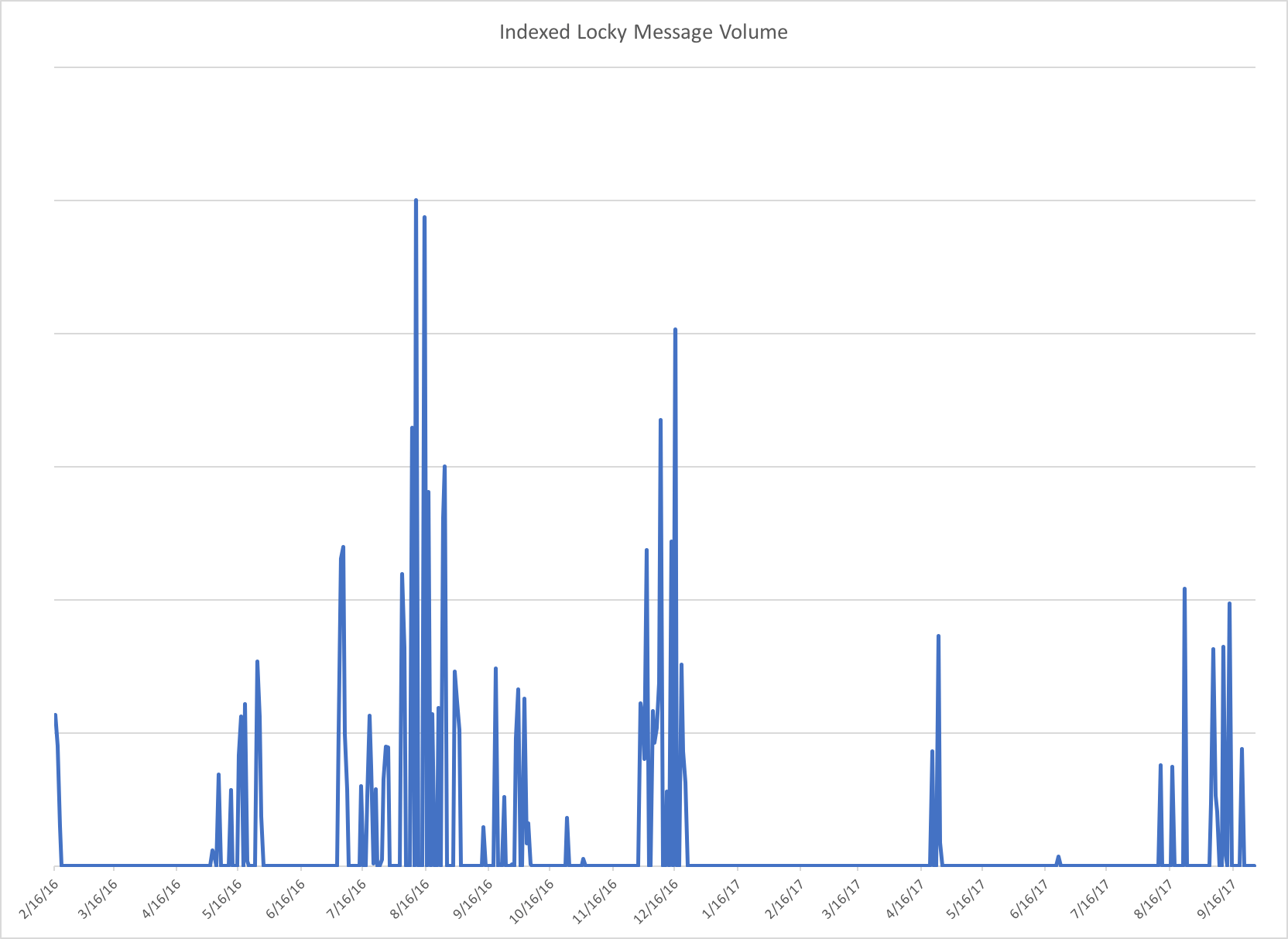

TA505 introduced Locky [7] ransomware in February 2016. After alternating for over four months with Dridex, Locky became the payload of choice for TA505, eclipsing earlier campaigns in terms of volume and reach. TA505 stopped distributing Dridex in July 2016, relying almost exclusively on Locky through December of that year. Like Dridex, Locky is also distributed in an affiliate model; TA505 exclusively distributes Locky Affid=3.

Figure 3: Indexed Locky message volume since TA505 began distributing the ransomware in early 2016

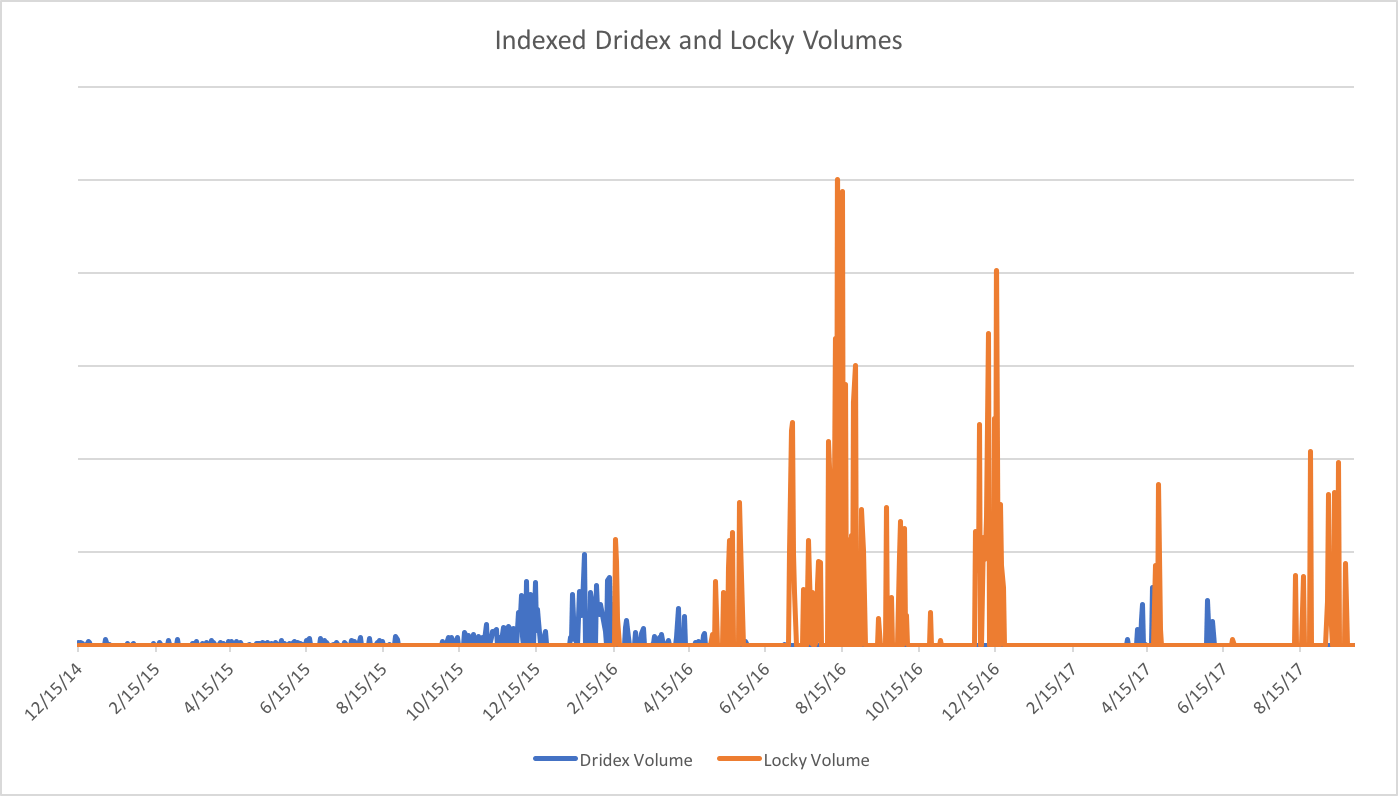

Figure 4 shows the evolution of Dridex and Locky campaigns over the course of over two years:

- Low-volume campaigns distributed Dridex during much of 2015

- Moderate volumes of Dridex appeared from the end of 2015 through February 2016; it is worth noting that these “moderate volume” campaigns were, at the time, the largest campaigns ever observed.

- Alternating Dridex and Locky campaigns of varying volumes appeared through May 2016.

- A lull in June 2016 [1] associated with a disruption in the Necurs botnet; TA505 is heavily reliant on this massive botnet to send out high-volume malicious spam campaigns and disappearances of TA505 activity frequently accompany disruptions in Necurs.

- Extremely high-volume campaigns distributing Locky exclusively in July 2016, consistently delivering tens of millions of messages.

- Another lull in November 2016 saw the complete absence of Locky and Dridex, while high-volume campaigns reappeared in December, albeit at lower volumes than during the Q3 2016 peak.

- An expected break following the 2016-2017 winter holidays turned into an unexplained three-month hiatus [8] for TA505.

- Large-scale Dridex and Locky campaigns returned in Q2 2017, although none reached the volumes we observed in mid-2016.

- Later campaigns saw new attachment types, even as Dridex and Locky payloads remained largely unchanged.

- Locky distribution ceased in June and July but returned in August with volumes rivaling the peaks of 2016.

- TA505 turned to URLs in early August 2017 to distribute Locky, finally eschewing the document or zipped-script attachments that have characterized the majority of their Locky campaigns since February 2016; most of these URLs linked to malicious documents and scripts.

- By later August, TA505 had turned back to large attachment campaigns, primarily distributing various zipped scripts that downloaded Locky. The group continued this pattern with occasional URL campaigns and attached HTML files bearing malicious links.

Figure 4: Indexed Dridex vs. Locky message volume since TA505 began distributing Dridex in early 2015

Rockloader

TA505 first introduced Rockloader [9] in April 2016 as an intermediate loader for Locky. At that time, Rockloader was the initial payload downloaded by malicious attached JavaScript files. Once Rockloader was installed, it downloaded Locky and, in some cases, Pony and Kegotip. Pony is another loader with information stealing capabilities while Kegotip is an credential and email address harvesting malware strain that would appear in a small number of TA505 campaigns the following year as the primary payload.

Bart

Bart ransomware [10] appeared for exactly one day on June 24, 2016. It was a secondary payload downloaded by Rockloader, the initial payload in a large email campaign using zipped JavaScript attachments. The Bart ransom screen was visually similar to Locky’s but Bart had one important distinction: it could encrypt files without contacting a command and control server. However, we have not seen Bart since, suggesting that this was either an experiment or that the ransomware did not function as expected for TA505.

Kegotip

TA505 briefly distributed the Kegotip information stealer in April 2017. Across two campaigns of several million messages each, the actor used both macro-laden Microsoft Word documents and zipped VBScript attachments to install the Trojan on potential victim PCs. Kegotip is an infostealer (credentials and email addresses) used to facilitate other crimeware activities. It steals credentials from various FTP clients, Outlook, and Internet Explorer. It also will gather email addresses scraped from files stored on the computer. This information can be used to facilitate future spam campaigns by the perpetrator or may be sold to other actors.

Jaff

TA505 introduced Jaff ransomware [11] in May 2017. Jaff was not dramatically different from other ransomware strains. The payment portal was initially similar to the one used by Locky and Bart. It was primarily notable for its high-volume campaigns and its association with TA505, given the actor’s propensity for massive campaigns and ability to dominate the email landscape. Jaff appeared in multi-million message campaigns for roughly a month and then promptly disappeared as soon as a decryptor was released in mid-June 2017.

The Trick

The Trick, also known as Trickbot, is another banking Trojan that TA505 first began distributing in June of 2017, although we have observed The Trick in the wild since fall 2016, usually in regionally targeted campaigns. It is generally considered a descendant of the Dyreza banking Trojan and features mutliple modules. The main bot is responsible for persistence, the downloading of additional modules, loading affiliate payloads, and loading updates for the malware.

As with much of the malware distributed by TA505, The Trick has appeared in frequent, high-volume campaigns. The campaigns used a mix of attached zipped scripts (WSF, VBS), malicious Microsoft Office documents (Word, Excel), HTML attachments, password-protected Microsoft Word documents, links to malicious JavaScript, and other vectors. The last TA505 campaigns featuring The Trick appeared in mid-September 2017 with payloads alternating between Locky and The Trick.

Philadelphia

Philadelphia ransomware has been circulating since September 2016. It first attracted our attention in April of this year [12] when we observed an actor customizing the malware for use in highly targeted campaigns. In a brief stint, TA505 distributed it in one large campaign in July, but we have not seen them use it since.

GlobeImposter

GlobeImposter is another ransomware strain that saw relatively small-scale distribution until TA505 began including it in malicious spam campaigns at the end of July 2017. TA505 primarily distributed GlobeImposter in zipped script attachments through the beginning of September 2017. Again, GlobeImposter is not particularly innovative but TA505 elevated the ransomware from a regional variant to a major landscape feature during roughly six weeks of large campaigns.

Conclusion

TA505 is arguably one of the most significant financially motivated threat actors because of the extraordinary volumes of messages they send. The variety of malware delivered by the group also demonstrates their deep connections to the underground malware scene. At the time of writing, Locky ransomware remains their malware of choice, even as the group continues to experiment with a variety of additional malware.

The history of TA505 is instructive because they

- Have proven to be highly adaptable, shifting techniques and malware frequently to “follow the money”, while largely sticking to successful strategies where possible

- Are flexible, using largely interchangeable components, innovating where necessary on the malware front and using off-the-shelf malware where possible

- Operate at massive scale, consistently driving global trends in malware distribution and message volume.

Each of these elements makes TA505 a magnifying lens through which to consider the framework employed by many modern threat actors. Such a framework typically consists of five elements:

- Actor: The attacker organization; real humans driven by various motivations -- In the case of TA505, the motivations are financial.

- Vector: The delivery mechanism; email via attacker-controlled or leased spam botnet -- Necurs for TA505 -- remains a dominant vector, and certainly the vector of choice for this actor.

- Hoster: The sites hosting malware; if malware is not directly attached to email, then macro-enabled documents, malicious scripts, or exploit kits will pull payloads from these servers. TA505 almost exclusively hosts malware in this way, although they vary the means of installing their final payloads on victim machines.

- Payload: The malware; software that will enable the attacker to make use of (control, exfiltrate data from, or download more software to) the target computer. For TA505, the payloads have shifted over the years and months of their activity, but their sending and hosting infrastructure make these changes relatively simple to implement.

- C&C: The command and control channel that serves to relay commands between the installed malware and attackers. TA505 operates a variety of C&C servers, allowing it to be resilient in the case of takedowns, sinkholes, and other defensive operations.

This framework enables attackers to operate in robust, horizontally segmented ecosystems, specializing in developing certain parts of the framework, and selling or leasing to others; such frameworks are resistant to takedowns and individual component failures. But such frameworks also increase attackers' detection surface, that is, their susceptibility to discovery. In the case of TA505, while most elements of the framework are well-developed, their reliance on the Necurs botnet for the sending high-volume malicious spam - a key component of the Vector element above - appears to be their Achilles heel.

By tracking each of these elements, defenders can infer other elements and take the appropriate defensive measures. We will continue to track this actor, which, despite significant occasional disruptions to their sending infrastructure, appears to be on track to continue driving the majority of malicious email in the months to come.

References

[3] https://www.secureworks.com/research/dridex-bugat-v5-botnet-takeover-operation

[4] https://www.s21sec.com/en/blog/2014/07/new-feodo-variant-follows-geodo-steps/

[5] https://securelist.com/dridex-a-history-of-evolution/78531/

[6] https://www.proofpoint.com/us/threat-insight/post/Not-Yet-Dead

[8] https://www.proofpoint.com/us/threat-insight/post/2017-q1-threat-report-findings