Overview

Point-of-Sale (POS) malware made headlines in 2013 with high-profile retail breaches that exposed millions of credit cards. POS malware is specifically designed to infect payment terminals at retailers, hotels, restaurants, and elsewhere. Traditionally, POS malware has scraped credit and debit card information from magnetic stripe readers or from memory on the terminals. Even with the widespread implementation of chip and PIN technologies, new POS malware has emerged that can calculate authentication codes for chipped cards and use them later for fraudulent transactions.

More recently, the dangers of POS malware have receded from view as banking Trojans such as Dridex and Ursnif caused headaches for businesses, while 2016 has been dominated by large-scale distribution of ransomware like Locky and CryptXXX. Shifting headlines, however, do not mean that POS malware has gone away. On the contrary, POS malware is alive and well, with actors regularly targeting multiple verticals with attempts to capture credit card information en masse for sale on the black market. With its “Black Friday” sales, Thanksgiving weekend demonstrated especially high levels of activity as network traffic for data exfiltration from infected terminals spiked by nearly 400% for some malware families.

Through all of this, email has become an important vector for distribution of POS malware to organizations, even if as a secondary payload for a loader or banking Trojan that provides a beachhead for deeper attacks on networked POS systems. In fact, the role email plays in both early POS malware distribution and modern campaigns is representative of broader trends in the use of email as an attack vector: between 2013-2014, POS malware was often distributed as a result of infections caused by clicking malicious links in email messages; between 2015-2016, malicious document attachments distributed POS malware and other payloads.

Analysis

The POS malware market is varied and evolving, with new tools emerging to take on improved retail security as well as to add functions that may be useful to attackers infiltrating networks that support retail and Point-of-Sale operations. Regardless of the mechanism of delivery, installation, or execution, we can generally observe contact with command and control (C&C) servers via a series of network sensors run by our Emerging Threats group. Figure 1 shows the top POS malware over 2016 based on C&C traffic and check-ins.

Figure 1: Top POS malware by indexed volume of network activity

While Figure 1 shows occasional spikes with a regular ebb and flow of network activity for several POS malware families, Proofpoint researchers observed 3-4x increases in data exfiltration traffic related to ZeusPOS and NewPOSthings variants over the Thanksgiving weekend. While increased traffic associated with Black Friday was expected, the spikes, shown in Figures 2 and 3, were dramatic.

Figure 2: Thanksgiving 2016 weekend network activity for ZeusPOS

Figure 3: Thanksgiving weekend data exfiltration activity for NewPOSthings

Although the spike in network activity around the Thanksgiving holiday in the US was noteworthy, a look at overall traffic patterns since the beginning of the year tells an equally important story. We observed considerable overlap among various POS malware families, suggesting cases of shared infrastructure (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Network graph showing relative activity and connections by POS malware family

Figure 4 in particular demonstrates that

- Like other forms of malware, POS malware activity tends to be concentrated around a few dominant variants, even as minor variants continue to make the rounds and wait in the wings to become "the next big thing"

- Major variants are often related by shared infrastructure or actors that move from using one variant to another, as happened with Dridex and Locky in the banking Trojan and ransomware spaces

- Establishing these relationships helps organizations better defend against POS malware by observing similarities in C&C check-ins, infection methods, etc.

In many cases, we can also associate malicious email campaigns with initial attempts to install POS malware. Figure 5 shows the relative volume of malware payloads targeting the retail vertical in October. Note that after removing Locky ransomware, which accounted for 90% of all message volume, the top two payloads were loaders: Pony and H1N1. It is also worth noting that we first discovered AbaddonPOS, a widespread POS malware variant, being spread by Vawtrak, the third-ranked payload in Figure 5. While these were not necessarily dropping POS malware, this chart shows that attackers have mature tools at their disposal, as well as databases of retail contacts, through which they can target retailers via email in order to attack POS systems.

Figure 5: Relative message volumes by payload targeting retail in October, with Locky removed for improved visibility

Taking a closer look at specific campaigns this year gives us additional insight into the distribution of POS malware and the changing landscape in this sector.

Personalized TinyLoader -> AbaddonPOS

The "personalized actor" or TA530 frequently engages in small to medium-sized campaigns that involve personalized emails and lures to increase their effectiveness. We observed campaigns from this actor targeting big-box retailers and grocery chains in July and October. The attacks involved thousands of messages dropping AbaddonPOS via TinyLoader. The attacker uses a personalized “client feedback” email with the recipient's name in the subject, attachment name, and email body that references a specific store location (Figure 6). This creates a socially engineered, legitimate-looking lure that entices users to open an attached Word document and enable macros. Enabling macros installs TinyLoader which in turn installs AbaddonPOS.

Figure 6: Personalized client feedback email lure featuring a social engineered complaint - "I am emailing you to submit my feedback about the bad treatment that I and my wife received at a store of [store name and location redacted]..."

We have previously observed TinyLoader leading to AbaddonPOS, but the campaigns were not personalized.

JackPOS

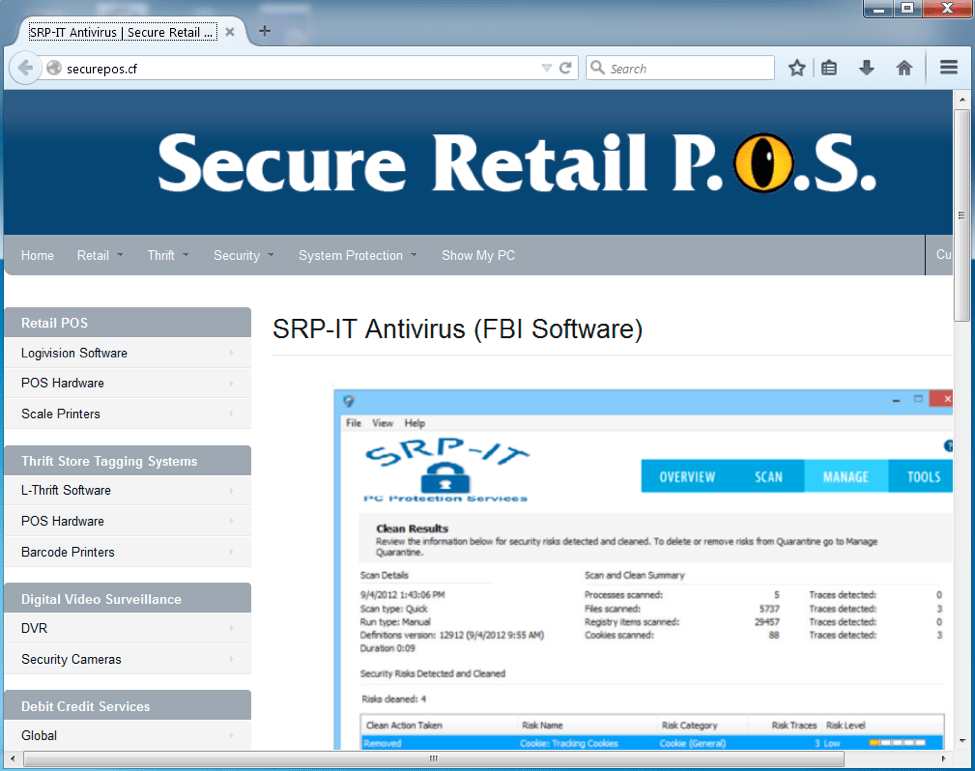

JackPos is a POS malware that attempts to scrape credit card details (track 1 and track 2) from computer memory. In April, we observed a campaign with thousands of email messages that contained malicious URLs linking to a compressed JackPOS malware executable. The executables were hosted on securepos[.]cf, which appears to be a fake page and a convincing front pretending to market ARP-IT Antivirus, Retail POS, and other products.

Figure 7: Fake website purporting to sell AV, POS software, and other tools, and hosting POS malware

Project Hook

In October, we observed a low-volume email campaign distributing "Project Hook" POS malware. Interestingly, this campaign was highly targeted at spas, with a link to a fake update for spa management software. Clicking the update link in the emails led to a compressed .vbs file that loads Project Hook, leading to the "update confirmation" in Figure 8.

Figure 8: Fake update confirmation for spa management software

Project Hook malware has been observed in the wild since 2013 and continues to make the rounds in various incarnations.

Kronos -> ScanPOS

Most recently, we observed a relatively large campaign distributing an instance of the Kronos banking Trojan. This campaign was highly targeted at the hospitality vertical, as shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9: Relative volumes for vertical targeting in the October Kronos -> ScanPOS campaign.

Once installed via either malicious macros in a document attachment or via a link to a malicious document, Kronos downloaded one of three secondary payloads, including a new POS malware variant called ScanPOS. ScanPOS is a relatively simple POS malware that scans memory processes for credit card numbers that are subsequently sent to a C&C server via HTTP POST.

These campaigns provide a snapshot of the current POS malware landscape and the tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) that threat actors are using to deliver the malware to their targets. A closer look at the campaigns reveals some common threads:

- Increasing degrees of personalization and targeting: whether actors are personalizing their lures to increase effectiveness or going after a very specific vertical with specialized bogus software, email campaigns provide a rich basis for attacks

- Fake software, websites, and email lures are sophisticated and compelling social engineered tools that go far beyond the basic credential phishing that characterized attacks on POS systems in 2013 and 2014

- Attackers are using a diverse set of approaches, ranging from malicious document attachments to a variety of malware loaders that have proven successful with banking Trojans and ransomware to deliver POS malware payloads.

Targeting Retailers Indirectly

Unfortunately, the threats to retail aren't limited to POS malware. We have also observed a significant uptick in retail account phishing attempts. The most recent use lures of payment for "secret shoppers" or online reviews and target students at higher education institutions who may be willing to enter credentials for a chance at some quick, easy money.

Figure 10: A fake customer satisfaction survey for an Australian supermarket chain

In other cases, actors use further variations of credential phishing to obtain login details for “big box” store and other retailer accounts, allowing them to conduct fraudulent transactions. Regardless of the method or particular retailer targeted, though, it is the retailer that will ultimately bear the costs associated with these transactions. While POS malware can net threat actors potentially very large paydays, higher volume credential phishing can also be quite lucrative and threatens retailers brands as well as their bottom lines -- and the pocketbooks of unsuspecting consumers.

Conclusion

Point-of-Sale malware continues to be distributed and operate at relatively high volumes. This isn't surprising given the potentially large payouts for threat actors if they can capture large numbers of credit cards. Even as the payment industry works to ensure PCI compliance and moves toward more secure credit card transactions with chip and PIN technologies, POS malware is evolving to work around these new barriers. At the same time, threat actors are innovating to deliver their payloads more effectively, diversify their approaches, or even cash in on simple credential phishing using retail brands as the lure.